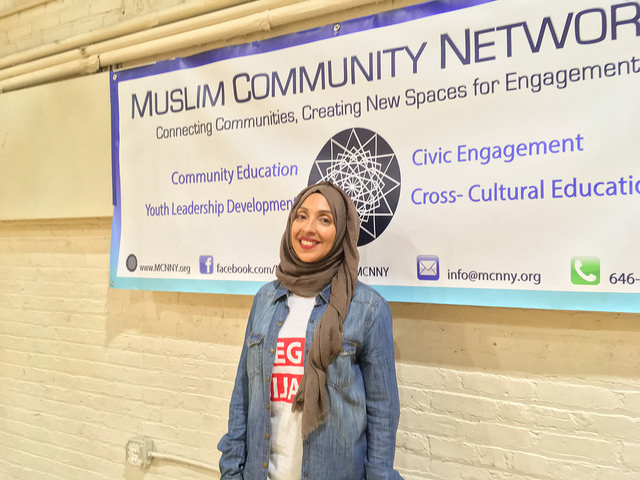

Nutritionist and personal trainer Zainab Ismail at a Women’s Self Defense Workshop in the West Village. Ismail has attended several self-defense workshops to discuss the profiling and harassment she says she faced several days after the 2016 presidential election. Photo by Razi Syed.

In the wake of the election, hate crimes against numerous religious, racial and gender groups have surged — with Muslim-Americans often facing the biggest brunt of the rise.

“Hate crimes have been steadily increasing as the political rhetoric has turned to divisive speech in the election,” said Afaf Nasher, executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, a civil rights group which monitors hate against Muslims.

In the first 10 days following the election, nearly 900 incidents of hate were reported to the Southern Poverty Law Center, a civil rights nonprofit.

In November, the FBI released its annual hate crimes report — the most thorough and widespread compilation of hate crimes nationwide — which noted a 6 percent increase in hate crimes in 2015.

While attacks on Jews made up the largest number of crimes based on religion, attacks on Muslims surged 67 percent, the largest increase over the one-year period.

The report gives context, but provides an incomplete picture as local agencies are not always reporting their hate crimes to the FBI, said Madihha Ahussain, a staff attorney at Oakland-based Muslim Advocates, which assists victims of anti-Muslim acts in understanding their legal rights.

“Law enforcement at the local level are actually not mandated to report — it’s all volunteer reporting,” Ahussain said. “And there’s a number of cities that choose not to report, or they will report zero. It’s hard to believe that as many cities that report zero actually had zero hate crimes.”

New York City may be a multicultural melting pot with residents coming from all corners of the world, but it hasn’t been immune from attacks on Muslims.

One day after the election, New York University had the Muslim prayer room in the engineering building vandalized with the words “Trump.”

Bay Ridge, Brooklyn resident Zainab Ismail believes her appearance as a hijab-wearing Muslim resulted in harassment on the part of NYPD officers in her neighborhood on Nov. 11.

Ismail claims she was parked in her car when she got out to walk to the gym and noticed that two police cars were double-parked two spaces behind her car.

“Then I saw a police officer, talking into his walkie talkie, stare right at me,” Ismail said. Two officers approached Ismail and asked if they could speak with her.

Ismail was informed that someone had called 911 and reported her as a “suspicious person” getting in-and-out of her car. Ismail was incredulous — she had gotten out of her car just once to make sure her vehicle wasn’t blocking a driveway, she told them.

Over the following several minutes, Ismail said she was asked to provide multiple forms of identification, asked for old utility bills to prove she lived where she said she lived and was informed by the officers that they had doubts about parts of her story before they let her go.

After reaching out to Council on American-Islamic Relations-NY, Ismail chose to file a complaint with the Civilian Complaint Review Board, which is tasked with investigating complaints about the New York City police.

“I did not record audio or video of my incident, so it’s really going to come down to my word against theirs’,” Ismail said. “However, with a full investigation, it will still leave a statistic.”

Though national data on hate crimes indicates an upward trend in recent months, Nasher believes the statistics represent only a small fraction of what actually occurs.

“When I go to do educational workshops,” she said, “almost always, I’ll will have a line of people who will talk to me after the workshop is done. And one-by-one, I’ll start hearing stories: ‘Do you know what happened to me? Do you know what happened to my kid?’

“And every single time, I’ll ask, ‘Did you report it?” Nasher said. “And the answer is, probably, 80 percent ‘no.’

“It’s really a two-way battle,” Nasher said. “There’s this severe underreporting within the community, which is something we are pushing to change; and then, there’s also the other side of it, and that is, in order to be categorized as a hate crime, it has to meet a certain criteria.”

Because of the high legal bar to clear for a successful prosecution under the federal hate crime law, Ahussain said the most typical successful prosecution generally involves vandalism, for instance, anti-semitic graffiti on a synagogue.

Muslim-Americans will have to be proactive in trying to break stereotypes about their community, Nasher said.

“I think it’s time for Muslim parents to wake up and understand what is going on around them and how it affects an entire generation of young people who were born after 9/11,”she said. “For a long time, African-American parents always had discussions — especially with their young, black, male youth — about walking down the wrong street while being black. I don’t want to make a parallel, because the African-American experience and what shaped it, is very unique.”

Nashar has a message for all children, be careful and be proud.

“Don’t let outside belittle you in a way that’s going to make you less observant in your faith, less true to who you are,” she said.”