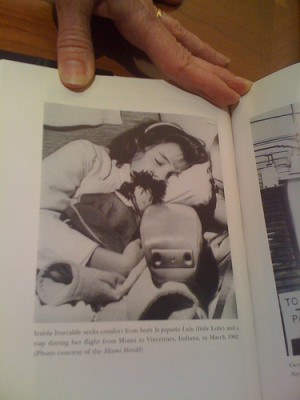

Iraida Iturralde, a Pedro Pan, is shown in a 1962 photograph from Yvonne Conde's book "Operation Pedro Pan." The snapshot, taken by a Miami Herald photographer, captured Iturralde on her way to Saint Vincent’s Orphanage in Vincennes, Ind. Photo by Emily Canal.

Iraida Iturralde remembers watching the buildings and landscape of Havana, Cuba melt into colorful blurs from the airplane window. She was a scared seven-year-old leaving home for the first time and unsure if she would ever return.

“The minute the plane took off I went berserk, because it was my first drastic separation,” said Iturralde, who works with the Cuban Cultural Center of New York. “What went through my mind was, ‘is this the last time I am going to see Cuba?’”

In January of 1962, Iturralde and more than 14,000 other Cuban children were airlifted from the island and taken to the United States. The exodus, Operation Pedro Pan, came on the heels of Fidel Castro’s communist revolution. With support from the Roman Catholic Church and the U.S. government, children whose parents opposed the revolution were taken out of the country.

“It’s the type of thing you learn to live with and turn it into a positive thing,” Iturralde said. “But there is something there that never heals.”

It has been 50 years since Iturralde’s mother sent her older brother, sister and Iturralde to the U.S. Her brother was separated from the family first. Iturralde and her sister, Virginia, arrived next.

After plans to stay with relatives in Florida fell through, Iturralde and Virginia stayed at specified camps in Homestead, Fla. Iturralde described one camp, called Florida City, as a collection of bungalows that divided the children by sex and age. Refugee Cuban couples were paid by the government to care for the children.

“There was a party going on and that was the first time I saw someone dancing the Twist,” Iturralde said.

Iturralde and her sister were then sent to Saint Vincent’s Orphanage in Vincennes, Ind., rumored among the children to be one of the worst places for the Pedro Pans.

“Kids used to say it was the worst place ever,” Iturralde said. “Where we were sent turned out to be just as bad.”

At Saint Vincent’s, Iturralde said she dealt with difficult nuns who struck her and grew frustrated with the language barrier. She explained how the Cuban children rallied together to overcome the hardships.

Iturralde, who now lives in West New York, N.J., said she has been searching for her foster parents online. So far, she has been unsuccessful.

Luisa Yanez, an interactive reporter with The Miami Herald, helped create a social networking site for people like Iturralde to connect and cope with their experiences. She said it has helped Pedro Pans tell their stories and find the people they met more than 50 years ago.

“Its therapy and closure and finding new friends,” Yanez said. “It does a million things that we didn’t think of when we created it.”

Yanez said the network, called Operation Pedro Pan, was created in 2009 for the 50th anniversary of the airlift. George Guarch, the arbitrator between the U.S. authorities and Cuban children, collected a comprehensive, hand-written list of names at Miami International Airport. The list was saved and housed at Barry University in Miami. After three months of work, The Miami Herald launched a searchable directory of names where people could connect with each other by sharing stories and photos.

“We are trying to create our own Ellis Island record for Cuban exiles,” Yanez said. “The database has taken on a life of its own and become a town center for all these Pedro Pans from across the country to find each other.”

A profile page on the site offers a Pedro Pan’s name, date of birth and the day they arrived in Miami. The site has 1,511 registered Pedro Pans and has been viewed nearly 3 million times.

Eloisa Echazabal, an assistant to the president in the medical campus of Miami Dade College, helped Yanez create the database. She said the event is a vital part of Cuban history and more people have learned about the airlift since the 50th anniversary and the website’s launch.

“This is a way for people to learn about this important part of history of Cuba and the U.S.,” said Echazabel, 63, of Miami, who is also a Pedro Pan. “And to learn how beautiful freedom is and when they loose it bad things can happen.”

Echazabel landed in Miami in 1961 when she was 13-years-old. She said the website also helps Pedro Pans piece together the details of their experiences, which can be hazy since the ages of the children varied drastically.

“There are 14,000 different types of stories,” Echazabel said. “I just learned to live through it, but I did cry many evenings and there is a lot of stuff I don’t remember anymore.”

Yanez said the network is the second of its kind in modern history. She said the only similar forum was created for Jews who escaped from Germany during World War II.

“There is an emotional hook to this database,” Yanez said. “Being a Pedro Pan, you are always a Pedro Pan, and that horrible experience marks you for life.”

Iturralde went back to Cuba four times, the last time in 1980 after her grandmother died. She said before she returned for the first time in 1979, she had a reoccurring dream that her body flew back to the island.

“I used to dream that I was floating down and landing in Havana,” Iturralde said. “It was my return, and I after I went I knew there was no way I can live there under this system. I never had the dream again.”

Comments

[…] Read more here LikeBe the first to like this post. […]