Sylvia Quinones sees retirement on the horizon.

“I keep telling them, I got two years here. That’s it. I’m retiring,” said Quinones, the current Test Chair and former ESOL (English to Speakers of Other Languages) teacher at Miami Jackson Senior High School. “But I don’t know. I’m an advocate for my babies and I love my kids. I don’t know if I can retire. I lose full time. I don’t know. I think I would miss fighting for them.

Although no longer in the classroom, Quinones knows of almost every student in Miami Jackson, especially those in the ESOL program. For a teacher who promotes “tough love”, dozens of the almost 400 ESOL students come to her office each day, sharing their test scores, an update in their program, or even just to converse in Spanish.

Miami Jackson is one of the many schools in southern Florida who have seen significant changes due to an influx of immigrant students in the past few years.

Quinones said that at Jackson, which has a population of about 1500 students, at least that more than half of the school had been ESOL at one point or another. About three years ago, the school saw a number of students in Jackson’s ESOL program, from its average of 250 to over 400.

“It’s very heartbreaking. But you know, we had one year that it was like 100 kids. I mean nonstop,” said Quinones. “We were at a point where we went over the 400 but we have a lot of in and out. Okay. They’ll come in, they’ll leave, they’ll come back or they go to another school and you know, that kind of thing.”

When students first enter the school, they must take an English proficiency test. If they qualify for ESOL, students take developmental classes and English classes, along with common curriculum classes such as math, science and history. In January, ESOL students take another exam to test their improvement. If their results deem efficient, students are then “exited” from the ESOL program, and start the next grading period by taking fully integrated classes with English speakers.

At Miami Jackson, it’s not uncommon for ESOL students to remain in the program for over four years, the average time of high school.

“Sometimes we’ve got to push them like the baby birds to make them fly and they’ve done well, very well,” said Quinones. “But usually it’s like three years . . .it’s three years when we start to think and say, okay, the grades are good, the testing is not so good. You know, some people don’t test well, okay, they can handle it. So we make decisions, you know, based on data, based on analyzing. You don’t live in there. It’s not a place where you go from ninth grade to twelfth grade.”

While certain schools such as Jackson can offer larger ESOL programs, teachers in other south Florida schools feel the weight of lack of resources.

Sarah Leonardi, a 10th grade English Literature teacher at Nova High School in Broward County, said with one ESOL coordinator for a student population of 2000 , accommodating students in her classroom can be challenging. She says that in her experience, students are expected to pick up English in class with native speakers.

“It makes it difficult when you’re trying to teach Shakespeare and this child who like got here last week is expected to sit in your class and read it and understand it and like pass tests,” said Leonardi, who incorporates multiple strategies to help ESOL students, including printing out Shakespeare in other languages. “It’s very discouraging to the kids and that’s how they’re learning English. It’s just like, it’s really, it’s not feasible.”

In the state of Florida, teachers are by law required to complete ESOL training if they have at least one English Language Learner (ELL) student in their classroom. But Leonardi, who is running the District 3 seat on the Broward County School Board, believes this training isn’t enough, and that having more resources such as more than one ESOL coordinator per school, are the solutions to helping students.

“There needs to be conversation about around like how and why these all students are expected to pass this English language arts test no matter like if they got here yesterday or they got here two years ago,” said Leonardi. “ I think that there needs to be a conversation about, providing classes where kids can learn English.and that’s just like school-based resources.

According to Karla Hernandez-Matz, president of United Teachers of Dade, in 2018 an estimated 10% of students in the Miami-Dade school district were immigrants, or over 34,000 students.

“Anytime that there is political unrest, we’ll see how that impacts our school system,” said Hernandez-Matz. “We try to make sure that we are able to provide not only opportunities for our workforce to be engaged, but also opportunities for the community to understand that we’re with them.”

In 2017, Miami mayor Francis X. Suarez, who is Cuban-American, made Miami a non-sanctuary city. Miami was the first city to comply with Trump’s executive order, after he threatened to pull funding from sanctuary cities. In response, the Miami-Dade school district, which includes over 100 nationalities, reaffirmed that anything school board property was deemed a safe zone.

“We’re really proud of that,” said Hernandez-Matz. “We know that our children were really concerned and parents were really concerned and although we never ask for an immigration status. We want our children to feel safe and the parents that are in the schools visiting or picking up their kids to feel safe as well.”

Alfonso Tetro, teacher with the Title I Part C Migrant Program in Homestead, said that fear has been prominent in his community, after several deportations of students’ family members.

“The kids were actually scared. Parents have been separated because of the deportation,” said Tetro. “And you know, and not because they did something, you know, most of these cases are because they, they just were caught by ice. And it’s traumatizing. “

The Migrant Title I Part C program provides additional educational programs for migrant children. In Homestead, the program caters to about 1,900 students on a 36-month school schedule, but the number can fluctuate depending on the crop season, according to Tetro.

Tetro, who grew up in a migrant family, was part of the Migrant Program as a child. Now he and his sister have both become educators, serving the community they grew up in. Tetro even works with students in Homestead High School, his alma mater.

For Tetro, some things in the program have changed while others have stayed the same.

“It’s a little different now because now honestly, immigrants weren’t looked down upon,” said Tetro.”It wasn’t an important issue, you know, because somebody needs to pick the field, somebody needed to work, whatever needs to be done. But people don’t see that now. Now they see them as a burden. Now what the current political climate is becoming. Like immigrants are bad.”

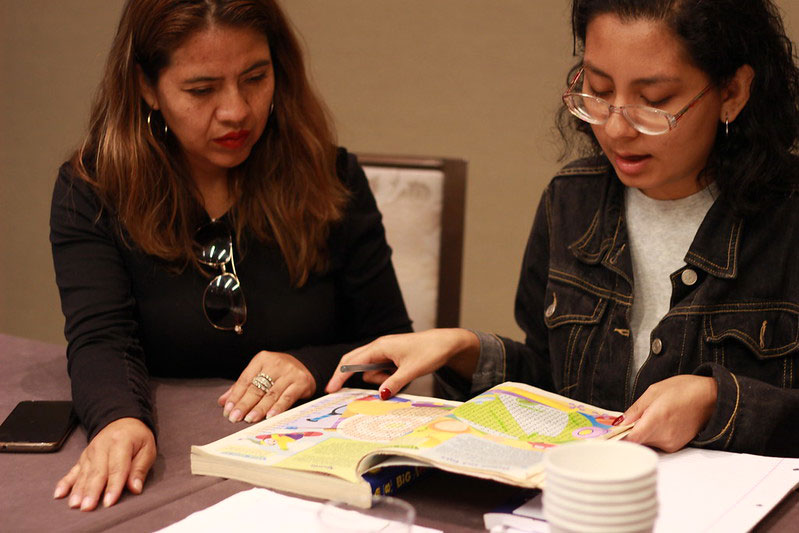

Nira Nova, 19, a student at Miami-Dade College, teaches a free ESL class to Rouss Salinas, a visitor from Peru. Nova teaches through her church, Church by the Sea in Bal Harbor. Nova intends to transfer to American University’s legal studies program. Nova’s mother came to the United States from Bogota Colombia while she was seven months pregnant. Photo By: Maureen Mullarkey.

Nira Nova, 19, a Miami-Dade College student, knows this first hand. A first generation Colombian-American, Nova was part of her elementary school’s ESOL program.

“I know what it’s like having parents that don’t speak English” said Nova. “I took English as a second language when I was in kindergarten because when I went into school I didn’t know any English and Spanish was my first language.”

Nova, who intends on studying law at American University, now volunteers teaching English as a Second Language at her church, Church by the Sea in Bal Harbor.

“It makes me really happy being able to make a difference in people’s lives, especially since as a first generation student,” said Nova. “We have a huge amount of immigration and unfortunately a lot of these people aren’t able to speak English. So for them living in the United States, it must be really difficult not being able to know how to defend themselves or how to represent themselves.”

For Quinones, her relationships with her students are the key ingredient to seeing her students succeed.

“We have kids that have no education in their country. We have kids that missed out on the basics even here, because mom and dad are not stable at home,” said Quinones. “They need to understand that kids are kids and that you have to reach kids in any way possible in every way possible.”