Andrew Aronstein, 46, stood behind his table of baseball cards and 8×10 photographs. He was in a conference room on the second floor of the Four Points by Sheraton hotel in Flushing, Queens, on the first Saturday of December.

The baseball season had ended over a month ago, but Aronstein, sporting a blue New York Mets t-shirt, had driven in from Westchester that morning with four boxes of photos and cards left over from his father’s sports memorabilia company to sell to Mets fans at the annual Queens Baseball Convention.

The QBC was a fan fest, organized by fans, for fans. The convention’s website described the day as “a mix of a Comic Con and a baseball card show.”

The conference room in which Aronstein was set up lived up to that description. Directly across from him, Brian Kong, a 51-year-old artist from Brooklyn, sketched a picture of José Reyes, the former Mets shortstop, ahead of Reyes’ autograph session that afternoon. In the corner, Jerome McCroy, 48, commonly known as “Jay Mac,” and the designer of the Mets’ famed “OMG” sign, sold replica signs and ornaments of his logo. Around them were sports memorabilia dealers, who displayed everything from autographed baseballs to pieces of Shea Stadium seats.

They all sat adjacent to the main panel room, where SNY’s Baseball Night in New York cast spoke to a crowd of fans, many of whom wore Mets jerseys of different styles, players and eras.

Aronstein, like many of the convention’s attendees, was born into Mets fandom. When he was eight, his father, Michael, took him to Game 3 of the 1986 National League Championship Series at Shea Stadium on Oct. 11, 1986. That day, Lenny Dykstra hit a walk-off home run to lift the Mets over the Houston Astros. Aronstein was hooked.

Driving Aronstein’s love for sports was his father’s company, PhotoFile. If you ask any collector of sports memorabilia, chances are he or she owns at least one PhotoFile product. From 1987 to 2020, they were the leading retailer of professional sports photographs. Their cornerstone product was the classic 8×10 print, perfect for autograph events like the QBC, where Reyes, among other Mets alumni, signed for fans. Hours before the shortstop’s scheduled appearance, the fans had left Aronstein with only one Reyes photo in stock.

“As a kid, I was always surrounded by 8×10 photos,” said Aronstein, who was surrounded by those same photos, among other things, spread across his table at the QBC.

Michael Aronstein, Andrew’s father, used to have a different company, TCMA, that made baseball cards. When he became a licensee of MLB, Michael was also able to obtain licenses for the NFL, NBA and the NHL. PhotoFile was born.

Michael’s son was a veteran of buying and selling sports photos. He sold them to kids at summer camp when he was 10. He sold them 36 years later at the QBC, four years after PhotoFile closed.

Selling sports memorabilia was a challenging business to succeed in, Aronstein said. It was difficult to obtain licenses. And when companies did, he often saw them fail to meet their minimums.

To Aronstein, some of his items were nothing more than leftover stock. To the generations of Mets fans in attendance, his stock was a goldmine of memories and a snapshot of sports collectibles from an era gone by.

“I still enjoy coming out here and talking to fans and selling photos to people that are excited about it,” he said.

Aronstein hasn’t left the industry. He has an eBay store where he also sells his leftover stock. He now works for Love of the Game Auctions — an auction house that specializes in vintage sports memorabilia.

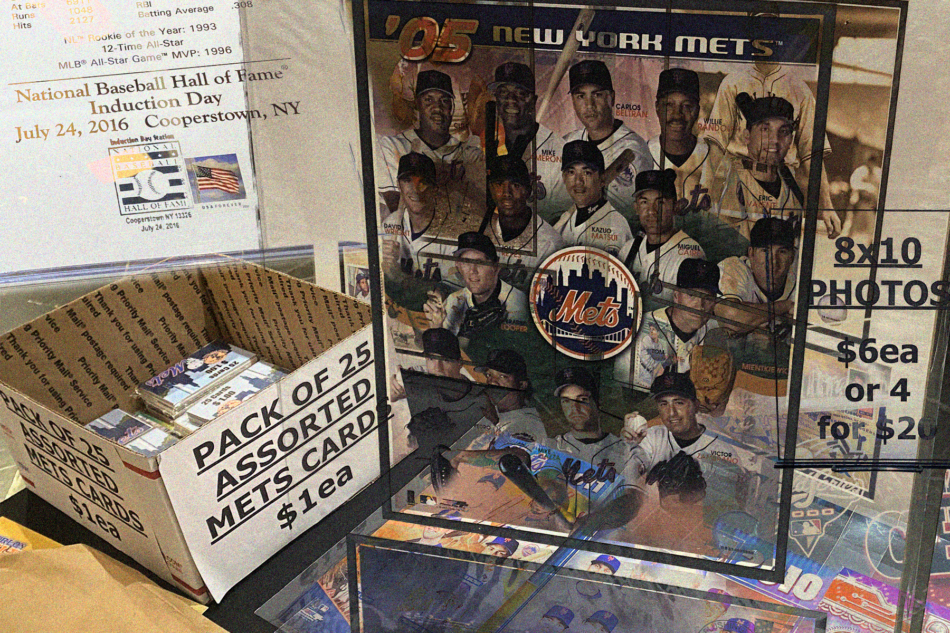

He sold packs of 25 assorted Mets cards for $1 — another idea of his father’s. The 8×10 photos, $6 each or $20 for four. Matted photos with an official first day cover, $8. A Dwight Gooden autographed ceramic tile, $20.

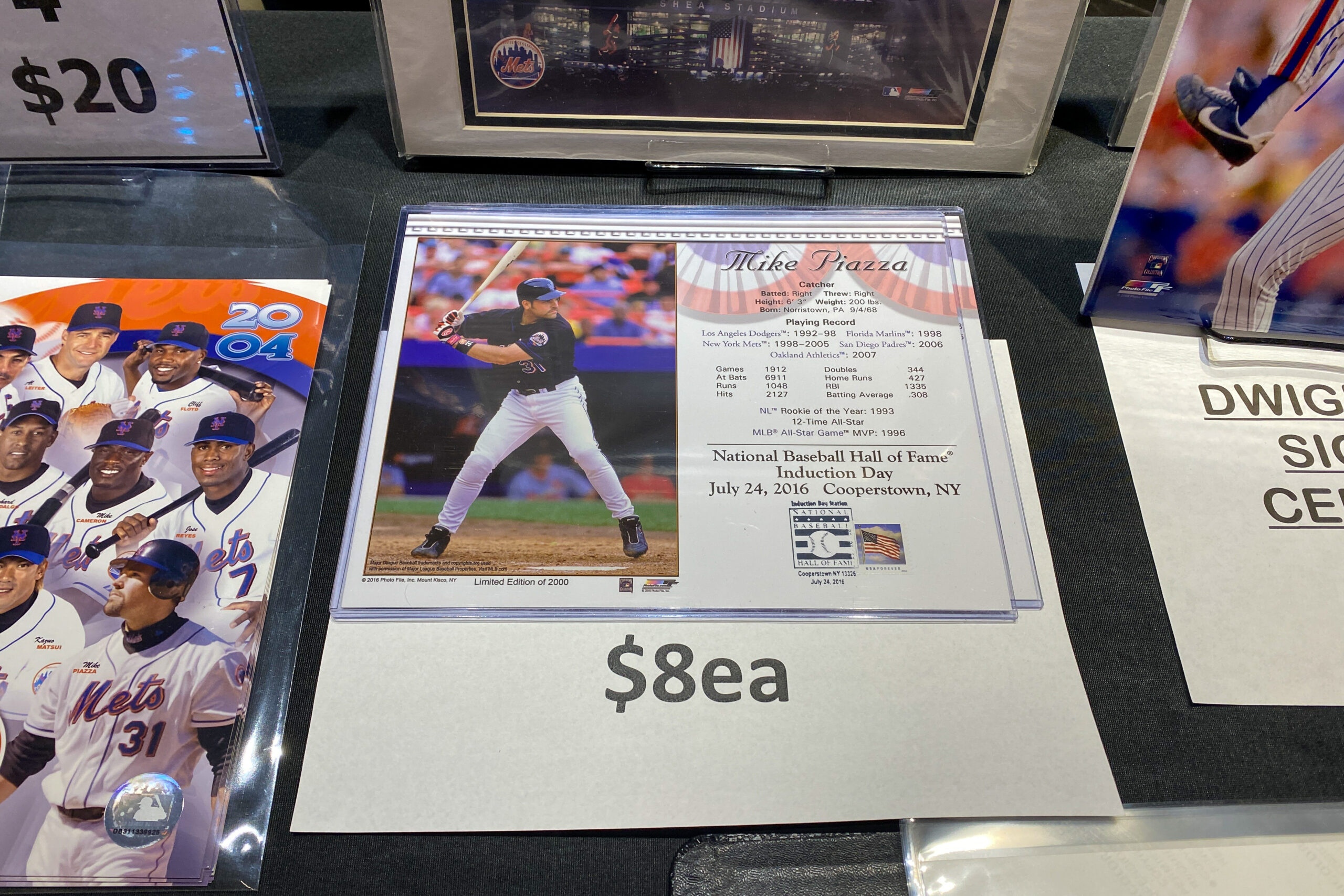

A Mike Piazza Hall of Fame card, postmarked on his induction date, at the Queens Baseball Convention in Flushing, Dec. 7, 2024. (Photo by Miles Bolton.)

The most intriguing pieces Aronstein had for sale were the Hall of Fame induction cards, which Rob Martinez, 29, stopped at as he browsed Aronstein’s inventory. Aronstein carried the two players that would interest Mets fans the most — Mike Piazza and Tom Seaver. At a trade show, he’d bring more.

“These are Mets Hall of Famers,” said Martinez. “It’s bittersweet, but you know how sweet it is, right? If only there were more players.”

The Hall of Fame cards were a brainchild of Aronstein’s father. They combined stamps and trading cards. In the mid-1980s, sports collectors were into what were then called event covers — more popularly known as first day covers — that were postmarked on the date of historic baseball events, according to Aronstein.

PhotoFile, of course, printed theirs on 8×10 sheets. Each one, limited to 2,000, was postmarked by the United States Postal Service in Cooperstown on the day that the featured player was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Alongside a photo of the player was a snapshot of his career stats.

Martinez fell in love with a different generation of Mets teams than Aronstein did. He grew up in the early-2000s and witnessed the rise of the 2006 team that pushed the St. Louis Cardinals to a Game 7 in the NLCS, before falling two runs short of the World Series. He cried when Carlos Beltrán struck out to end the Mets’ run.

Martinez also collects and creates sports memorabilia. In 2020, he began designing New Era 59Fifty fitted hats as a passion project. It eventually became a side hustle, then a “full blown dream,” he said.

The hat he wore at the convention was one of these designs. It had a black upper. A blue brim. An orange button. On the front, in white and outlined in metallic orange was the “New York” tail script, used only on the Mets’ road uniforms in 1993 and 1994.

Rob Martinez’s custom New York Mets hat featuring the “NEW YORK” tail script used by the team in 1993 and 1993 at the Queens Baseball Convention in Flushing, Dec. 7, 2024. (Photo by Miles Bolton.)

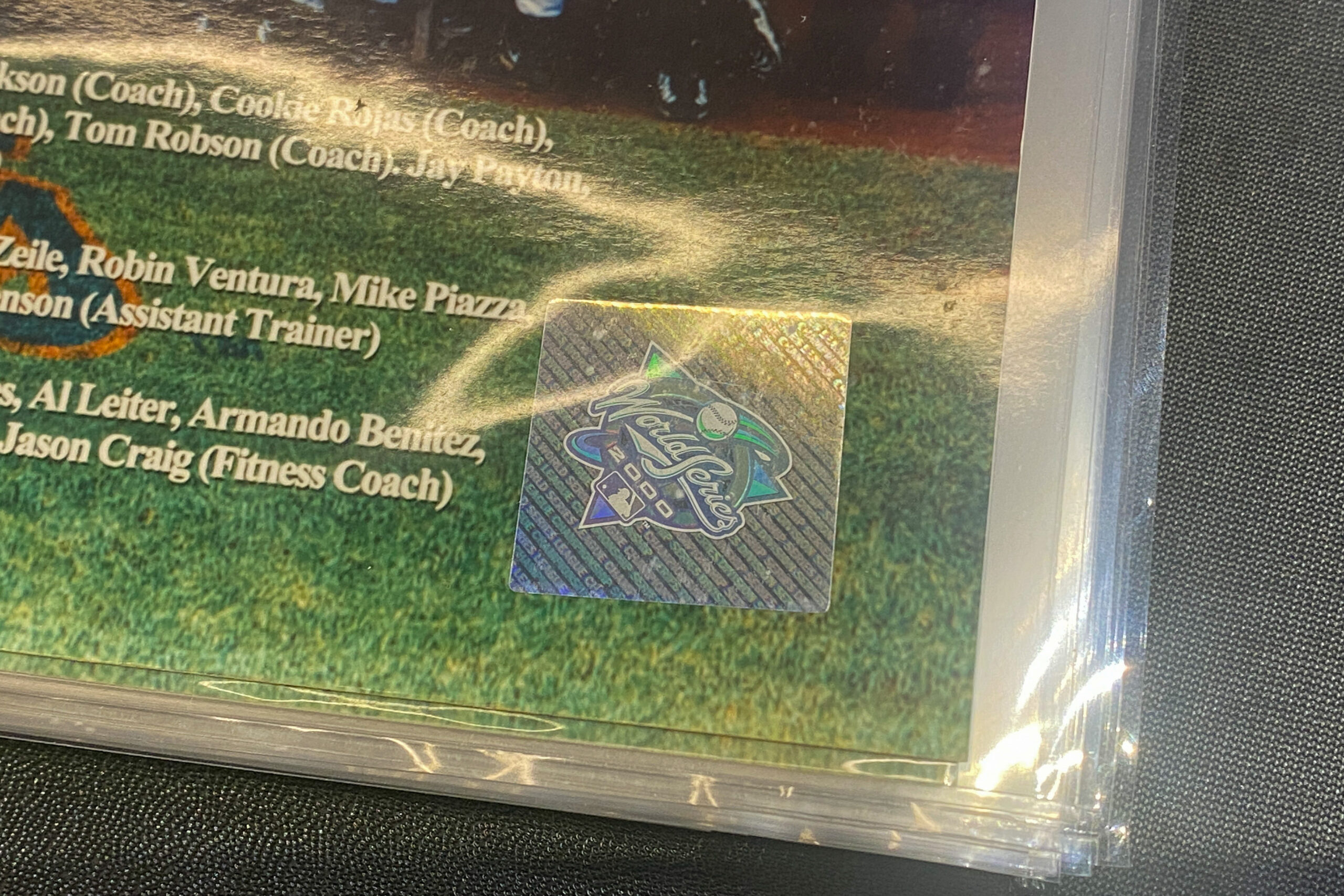

Martinez turned his attention to the black binder of 8×10 photos that was placed on the corner of Aronstein’s table. He flipped through it. He stopped on a team photo of the 2000 Mets commemorating their National League pennant.

“And I love this World Ser-” said Martinez, pointing at the shiny World Series hologram affixed to the bottom right corner of the photo. “I love that. The hologram.”

“Every year,” said Aronstein. He turned away for a moment to greet another customer.

“So at PhotoFile,” he continued, moving his hands apart. “We used to have a roll.”

“And on that roll were rows of holograms for every World Series. So every time we’d print a photo-”

“You’d have a hologram for the World Series,” said Martinez.

“Yeah,” said Aronstein. “So whichever World Series it’s from, we stick the hologram on it.”

A hologram featuring the 2000 World Series logo, used by Andrew Aronstein’s father’s company, Photofile, at the Queens Baseball Convention in Flushing, Dec. 7, 2024. (Photo by Miles Bolton.)

Martinez had to get the 2000 World Series photo. It was a fitting add for a sports logo aficionado who loved studying the branding history of the Mets and MLB.

“This is one of the best World Series patches ever,” he said. “Arguably one of the most thoughtful, just thought out designs.”

Martinez spoke with some authority. He worked with historic Mets and baseball logos when he designed his hats. He had catalogues of World Series and All-Star Game patches, he said.

An aspiring, independent hat designer faced challenges, in large part because of how the industry worked.

Martinez was comfortable working as a third party designer. There was no headache of ordering and selling certain styles or teams, confined by a contract like the major sports stores. His focus now was growing his business — a venture he spoke about passionately.

“I’ll show you a design that I made,” Martinez said.

He reached for his phone and navigated to his Instagram page, “@hatsofqnz.” He opened up the design of a purple hat with a remixed logo of the Queens Kings — a former minor league affiliate of the Toronto Blue Jays — in Mets colors. On the side was the Mets’ skyline logo.

“It’s using their logo,” said Martinez. “But it’s also using the Mets logo.”

Creativity had become a lost art in a world of mass-produced logos, hastily designed to get merchandise into fans’ hands quickly. The modern World Series logos are a simple blend of text, the year and either a graphic of the Commissioner’s Trophy or a waving pennant. Gone are the days of the leaves, last seen in 2012, that embraced the series’ “fall classic” nickname. And the baseball circulating the globe, as seen in the 2000 edition, hasn’t been used since 2003.

“You got to appreciate the designers,” Martinez said. “They’re the ones that are actually thinking it out. This isn’t really something you see anymore.

“You look around, most people have normal Mets hats on,” he said, gesturing at the few classic blue and orange caps scattered around the conference room. “But you look at me, you’ve never seen this on anybody.”

Martinez had something that no one else had. That was the magic of creating, curating and collecting sports memorabilia. At an event like this, he could share his designs. Aronstein could sell his photos to fans. Collectibles brought fans together, like first edition comics or Funko Pop figurines would at Comic Con.

Fans like Aronstein and Martinez, who was nearing a decision on what he’d soon be adding to his small collection of baseball memorabilia, mostly cards and figurines.

“I’ll take this one,” Martinez said after a long contemplation. “The 2002.”

He pointed at a matted composite photo of the 2002 Mets with an envelope commemorating the team’s 40th anniversary.

“And I’ll take one of these,” he continued, tapping the 2000 World Series photo. “If you wanna put ‘em to the side, I’ll just grab ‘em later.”

“Sure, yeah,” said Aronstein. We’ll just do that.”

“Just … I want to put ‘em aside.”

Martinez reached down and unclipped the black binder of photos. He carefully slid out the World Series photo. He handed it to Aronstein, who placed everything on top of a cardboard box behind the table.

“I’ll have it right here for you,” said Aronstein.