Chong Bretillon has been a bicyclist in New York City for four years. She regularly makes the trek from her home in Long Island City to Manhattan for work. But if she wants to take a Citi Bike to Flushing to pick up groceries at her favorite Korean store, she’s out of luck.

“I can’t go to Flushing, which is where I need to go to get Korean groceries and Korean food. I have to have my own bike or I have to take public transportation,” she said.

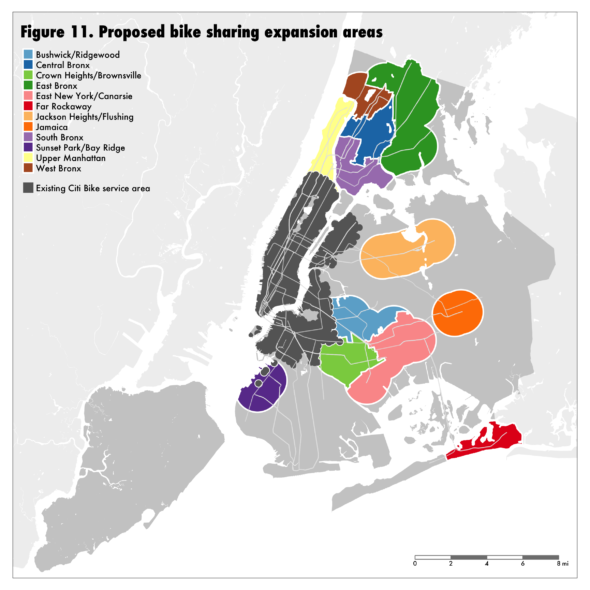

Neighborhoods like Flushing and Jackson Heights in Queens, Brownsville and East New York in Brooklyn, and Soundview and East Bronx in the Bronx are among the many neighborhoods across New York City without access to bike share programs like Citi Bike.

It’s what Bretillon calls “unfair placement.”

“The placement of Citi Bike docks and the whole map is very unfair,” she said. “It favors Western Queens, for example, which are neighborhoods that skew wealthier, more educated, more white,” she said.

Bretillon started out using Citi Bikes to commute to and from work, crossing over a railyard in Sunnyside and over the Queensboro Bridge to CUNY where she works as a professor.

But peddling the 45-pound bike over the bridge every day to an inconvenient docking station soon grew “unwieldy,” and Bretillon, 41, decided to buy her own bike.

“I wanted a zippier ride, to be able to lock it up anywhere. A lot of times, Citi Bike docks are not located conveniently, they’re not located where I want to go a lot of the time. So I needed my own bike,” she said.

A 2019 study by Urban Politics and Governance, a research group at McGill University, showed that Citi Bike “serves the wealthiest, most privileged part of New York City.”

Meanwhile, more than 70 percent of neighborhoods with a median household income under $20,000 lack access to bike sharing.

Disparities for New Yorkers of color are even greater. 83.5 percent of New Yorkers of color don’t have access to Citi Bikes, and only 94,000 of the 2.5 million New Yorkers that live further than half a mile from a subway (3.8%) have Citi Bike stations.

Citi Bike was launched in 2013 as a public-private partnership between several companies, and doesn’t receive any subsidies from the city, despite pressure from council members to do so.

Marketa Mala, a graduate student, resident of Crown Heights, and bicyclist filled out a Department of Transportation questionnaire on Facebook in September of 2021 about where residents of Brooklyn’s community boards 3 (Bedford Stuyvesant), 5 (East New York), 8 (Crown Heights), 9 (Crown Heights), and 16 (Brownsville) wanted to see Citi Bike next.

She was excited when she saw the questionnaire because she doesn’t have a Citi Bike dock near her, even though there are docks on the western border of her neighborhood.

“Around Prospect Park there are all the stations, so it’s unfortunate that we are just a few stops from that, but unfortunately, we still don’t have it,” she said.

Mala commutes to and from New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering in Downtown Brooklyn with a bike she bought on Facebook Marketplace for $150, just $35 shy of the $185 annual Citi Bike membership price, which she said she would not have purchased had she had access to Citi Bikes.

“If Citi Bike was here I would probably rather have the membership because of the advantage that anywhere in the city I can go and I wouldn’t need to plan so much, like, where do I take my bike?” she said.

Expansion efforts have been slow to reach the neighborhoods addressed in the expansion plan, in part because Citi Bike does not receive subsidies from the city, and therefore, is not included in the annual budget that would ramp up expansion.

According to Cory Epstein, the Director of Communications at Transportation Alternatives, a non-profit for safer streets that worked to bring Citi Bike to New York City, public funding wasn’t initially available at the time of Citi Bike’s launch because ride share programs were a fairly new concept and New York City was still recovering from the recession.

“Bike Share was really new and no one knew how it would work,” he said. “But considering we know how much it works now, considering our different financial position, and considering that so many cities across the country have added public funding to expand their systems, we think it just makes sense for to expand it and use more public money to get it to expand quickly, make it more affordable and more accessible.”

A poll from Siena College published last year found that 63 percent of New York City voters support public funding for bike share, a sentiment Bretillon shares, especially because it could mean more access to bike share for low-income New Yorkers.

“If we had municipal bike share that was owned and operated and maintained by the city, they’d be able to make it practically free. I mean, it should be free,” she said.

Lyft, Citi Bike’s parent company, did not respond for comment.