On Mondays, Cayln Dolan, 23, walks her 12th grade English students through a goal setting exercise, asking each of them to write down a goal for the day, a goal for the week, and a goal for the month,

“A lot of my boys will say their goal for the day is to make it to tomorrow,” she said.

For teachers like Dolan on the South Side of Chicago, keeping students safe from the gang violence that permeates their everyday lives tops the already demanding list of responsibilities bequeathed to them as educators. Dolan estimates that in her school alone, 80% of kids have been directly affected by gang-related violence. Challenging enough to address alone, gang violence is not the only problem that plagues Chicago Public Schools. With nearly 400,000 enrolled, making it the 3rd largest public school district in the nation; only 66% of students are meeting or exceeding educational standards, and with new challenging Common Core guidelines introduced statewide this year, bringing already struggling students up to par with state requirements has become increasingly difficult.

VIOLENCE IN CHICAGO’S SOUTH SIDE STORIFY

Special education instructor Eliza Bryant, 23, at Roberto Clemente Community Academy, a high school in Chicago said Common Core is based on literacy which her students struggle with.

“In the long run this will be beneficial, but for our students where everything we do is to make up for a lack of literacy, we just don’t have the foundation to begin with.” Bryant said

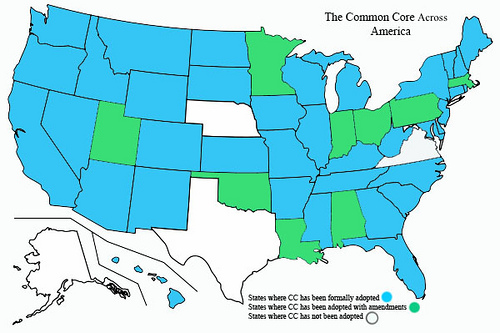

Common Core is a national program that states may elect to adopt, establishing principles to be reached at each grade level in reading and math. The idea is to ensure that high school students are ready to pursue two-or four-year degrees post-graduation. Forty states have adopted the guidelines which are meant to bridge the achievement gap by creating across the board expectations measured each year by assessments. Unlike No Child Left Behind, which was a mandatory federal law, states can choose whether or not to implement Common Core, and may amend any standards to best fit their state’s needs.

While many educators agree this is a good idea in theory, it is complicated in practice. For elementary school aged children in high-needs urban areas, reaching these standards may be challenging, but not impossible, as they have not been in the school system long enough for major gaps in achievement to have formed. However, for older kids who have been struggling in urban schools for a longer period of time, the Common Core is difficult to execute; any gaps in their education have been in place for years. Bryant, believes that the Common Core is key to helping teachers understand what skills students need to be practicing, but enforcement is problematic.

“The rigor of [Common Core] standards can be difficult, sometimes we have kids who are so low that meeting them isn’t even possible. I mean, I have students who can’t read consonants next to each other,” she said.

As with any newly introduced educational standards, the adjustment period is expected to be rough, and in consideration of this, assessment for the Common Core will not be implemented until the 2014-2015 school year. However, for teachers, whose jobs depend on the ability of their students to succeed on standardized testing, this gives them only a small window of time to close large gaps in education.

“Right now it’s a shift, in time it will be great,” said Susie Stoner, 46, principal of Barack Obama K-8 School in Milwaukee, Wis., where the Common Core is also newly in place this year. With over 20 years of experience in the struggling Milwaukee Public School District, Stoner believes Common Core standards will help level the playing field for many struggling urban students in the future.

For now, though, the rigorous academics enforced by the standards are a challenge for students and educators alike in low performing schools.

“The Common Core is not written to students’ instructional levels, but their age level. I have 7th and 8th graders who are not reading, so this can be very frustrating,” said Tom Sheehan, 31, a middle school special education teacher at Leslie Lewis School of Excellence in Chicago.

Other educators find themselves grappling to remedy the confidence blow standardized testing delivers to students who are already floundering. Dolan feels that it’s important to track students’ progress, but when students see their scores, all she sees is the disappointment that they bring.

“My kids are already statistics in so many other ways,” she said. “This just reinforces that.”

At the heart of the achievement gap are gaps in funding, which play a major role in the ability of teachers to meet students’ diverse needs. Stoner sees many of the issues her students experience reaching standards in testing stemming from the simple lack of resources that most urban school districts face.

“There’s not enough hours, there isn’t enough money, and there aren’t enough resources,” Stoner said.

But where resources are lacking, teachers make up in resourcefulness. Despite the obvious hardships that come with teaching in urban areas, educators are finding ways to inspire, encourage, and bolster students’ learning and emotional growth, and their hard work is starting to pay off. Just last year Chicago Public Schools boasted its highest recorded graduation rate since 1999, and dropout rates have been steadily declining as ACT scores have been slowly but steadily increasing.

In ‘turn-around schools,’ (failing schools given a second chance after low standardized test scores, and performance have them slated for closure), teachers and staff are educated on the importance of using language that encourages learning. The idea is to frame the message that education is key to a student’s success in life.

“Before in a school you might hear a teacher say ‘If you finish this test you get free time on the computer,’ it was a behavioral management thing, but then kids would rush through standardized testing to play on the computers,” Sheehan said. “Instead teachers are being taught to say, ‘Let’s work as hard as we can to finish this test so you can get into the high school you want,’ its all about framing.”