The Biden administration can continue deporting Haitian families after a Washington D.C. circuit court granted the administration’s request for stay on an injunction against Title 42 on Thursday. Title 42 is a Trump-era order that allows Customs and Border Protection to deport migrants in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

“It’s really cruel to be deporting these women, children, and families knowing that you’re sending some people to be killed,” said the Executive Director of Haitian Women for Haitian Refugees Ninaj Raoul.

The deportation of migrants under Title 42 is not new. More than 104,000 people have been deported under Title 42 since March 2021.

On June 30, Physicians for Human Rights wrote a letter to President Biden demanding he stop using Title 42 to deport families, citing the 3,250 documented cases of kidnappings, rapes, and other attacks against people deported or detained at the U.S.-Mexico border since taking office.

Despite efforts like PHR’s letter and the injunction against Title 42 by U.S. District Court Judge Emmet Sullivan, deportations of families will continue.

Outrage ensued after the image of a border patrol agent on horseback allegedly whipping a Haitian migrant at an encampment near the Del Rio International bridge was released, and coverage of the 14,000 migrants who gathered under the bridge situated at the Texas-Mexico border in September began.

Since Sunday, Sept. 19, over 6,000 migrants have been deported from the U.S. to Haiti, said Laurent Duvillier, the Regional Chief of Communication for Latin America and the Caribbean at UNICEF.

“Haiti is not just facing one crisis, it’s a combination of crises from political instability, but also increased gang violence over the past few months,” said Duvillier.

Various United Nations agencies have warned against deporting migrants to Haiti given the country’s instability in the wake of the assassination of President Jovenal Moisie and “dire” circumstances as a result of a 7.2 magnitude earthquake, according to a report by CNBC.

Duvillier has been on the ground in Haiti providing humanitarian aid to the deportees. According to recent data Duvillier received, 49 percent of migrants expelled to Haiti are women and children.

These women and children, Duvillier said, are “extremely vulnerable” to the uptick in violence in recent months.

According to the United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti, between January and August 31, there have been “944 intentional homicides, 124 abductions, and 78 cases of sexual and gender-based violence…with at least 159 people killed as a result of gang violence, including a four-month-old infant.”

Raoul said the situation in Haiti is especially dangerous for women, who are at risk of gender-based violence.

“There’s a lot of kidnapping and rapes going on right now,” said Raoul. “It’s like a rape epidemic.”

Raoul has been working at HWHR for 29 years, and in her time at the organization, she said she has never seen the kinds of numbers of deportations that have occurred over the past two weeks.

“We’re at record numbers of deportations here, including women and children, small children in particular,” said Raoul.

Over 40 children with non-Haitian passports have been deported to Haiti. These children do not have Haitian passports because many of the Haitian migrants at the Texas-Mexican border came from countries in South and Central America, where they had lived, worked and raised their families for years prior.

“Many of the children below the age of 10 were born either in Chile or in Brazil,” said Duvillier. “And they don’t speak Creole, they speak Spanish or Portuguese because their parents wanted them to get integrated in Chile or Brazil. So, we have a situation where we have many kids arriving in Haiti, in a country that they don’t know, not speaking the language, which makes them increasingly vulnerable to gang violence, but also to smuggling and human trafficking.”

Raoul said she was not surprised that there were thousands of Haitian migrants at the border, as “it’s basically what’s been going on for the past five years.”

She explained that many Haitians left the country after the 2010 earthquake and were welcomed by countries like Brazil who offered humanitarian assistance and jobs.

In 2015, however, Brazil faced an economic and political crisis and “started pushing the Haitians out, we don’t need them anymore,” said Raoul. “And people started heading north. They walked through nine or 10 countries, mostly by land and sea to get to the Mexican border and started coming up here in 2016. So that’s when we started seeing a large surge.”

The journey to the border was arduous for all migrants, but especially for women, many of whom were raped along the way.

“These people are survivors,” said Duvillier.“They’ve witnessed extortion, smuggling, violence, rape and then reaching the U.S., they were expelled.”

Raoul said migrants are often deported because they are denied credible fear interviews which would determine if they are eligible for asylum. She worked as a translator with the Department of Justice at Guantanamo Bay during the Haitian refugee crisis in the 1990s where she conducted credible fear interviews with Haitian refugees.

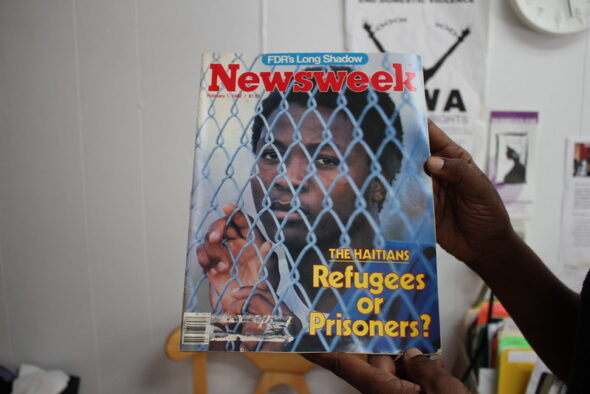

In her office, Ninaj Raoul holds a copy of Newsweek magazine from February 1, 1982 that depicts a Haitian refugee at Krome detention center. Photo by Annie Jonas.

“The credible fear interviews that we were translating for are pretty much identical to the same credible fear interviews that are supposed to be given at the border right now,” said Raoul. “I feel like we’ve gone full circle with the situations 29 years ago today.”

The road to asylum and resettlement in the U.S. is not an easy one, even for migrants who are granted asylum based on their credible fear interviews.

Raoul said the court systems that review migrants for asylum is just deporting them.

“So that means they’re going to go before a judge,” she said. “They’re going to be given a date to go before a judge, and the judge is going to say ‘why should I not deport you?’”

To ensure asylum seekers show up to their court dates, courts require seekers to wear electronic ankle monitors similar to those used on people who are incarcerated or on probation.

The monitors are known to negatively impact asylum seekers physically and emotionally.

“For us Black people, it reminds us of slavery,” Raoul said. “We call them ‘electronic shackles.’”

She said the use of electronic ankle monitors is part of the criminalization of Black immigrants, who are more likely to be deported than other immigrants, according to a report by the Black Alliance for Just Immigration.

Both Haitian migrants deported back to Haiti and those granted asylum in the U.S. face an uncertain future.

“These families, children, and individuals are basically looking for life, they are migrating for survival,” said Raoul.