As a teenager, Eva Bonsu begged her mother to allow her to put relaxer in her hair. She wanted the chemical to do what it did for millions of other Black women. She wanted her hair to be long and silky because she didn’t like the tight curls that adorned her head. Growing up, the lack of representation in arts and media influenced Bonsu’s decision to straighten her hair.

“I used to hate my hair, and it is kind of crazy when you have a little girl who grows up hating a part of herself,” she said.“I grew up seeing people in cartoons and movies with euro-centric features and straightened hair.”

Eva Bonsu’s perspectives on hair have evolved after years of trial and error. 2/22/2021. Photo courtesy of Eva Bonsu

Bonsu was a fan of Pocahontas who had brown skin, but hair was silky straight.

“I grew up with those images and felt that I needed to change that, and as soon as my Mom said that I could perm my hair to get it straight, I did it and it made me feel beautiful,” she said.

Bonsu was 14 when she first felt the sting of chemical relaxers and the smooth hair that resulted. For years it made her feel confident, but she decided to cut off her hair and go natural because could not find anyone in the small town of Macon, Georgia who could do her hair and she became part of the natural hair movement.

The movement encourages Black women to embrace Black hair free from wigs, extensions, or chemicals that could cause damage to their natural hair roots in the long run. The natural hair movement began in the 60s as a political statement for Black activists. The movement permeated the 70s and dissipated in the 80s after Black people with afros started to be targeted for their activism against racial oppression. The trend took off again in the mid-2000s. It was accelerated when notable Black celebrities like Erykah Badu, Lupita Nyong’o, Janelle Monáe, Solange Knowles, Tracee Ellis-Ross, and Viola Davis began to wear natural styles.

According to Mintel, a market intelligence agency, 40 percent of Black women reported that they were most likely to wear their hair in its natural form without any added heat, while 33 percent of Black women said that they would wear their hair in its natural form, but also use added heat to straighten their hair.

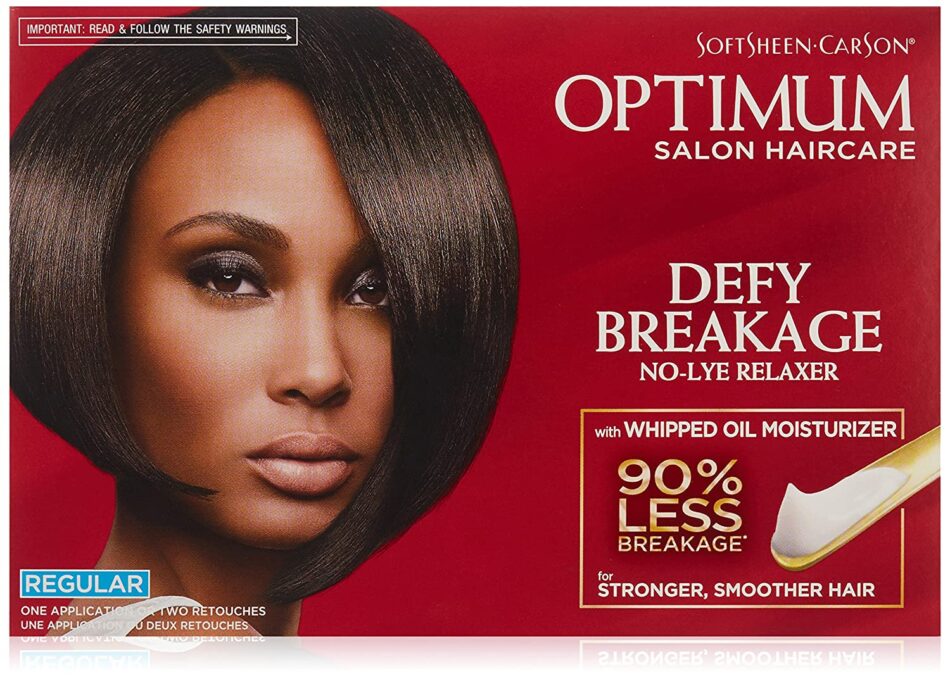

Although a Mintel study shows that hair relaxer sales have dropped by about 22.7 percent since 2016, and more Black women are wearing natural styles, it comes at a steep cost for some Black women in professional spaces.

Susan “Susy” Oludele, a Nigerian-American New York-based celebrity hairstylist who has worked on unique hairstyles for Beyonce and a bevy of other celebrities, said that many of her regular clients often complained about being discriminated against at work because of their hairstyles.

“There was a time when almost every other client I had would complain about the discrimination that they faced in the workplace because of their hairstyles, and I thought to myself, ‘this is crazy.’ I couldn’t understand it,” she said .

Oludele said that there was a time that one of her clients had to spend over $800 on her hair because her employer disapproved of it.

“I did auburn-colored braids for one of my clients who works in the tech industry, and she paid $400 for those braids, but I soon noticed that she set up another appointment, and I later found out that she had to take down the braids I had just recently done and pay an extra $400 to have them re-done because her employer didn’t approve of the color,” said Oludele.

Because of the discrimination that many of her clients were experiencing, Oludele teamed up with OkayAfrica to draw awareness to the plight of Black women experiencing discrimination because of their hair choices.

Historically, Black workers alleging discrimination against their natural hair in the workplace have filled courthouses for over four decades. Still, these allegations often produced mixed results. The judicial rulings, intertwined with changing socio-cultural standards, have yielded a contentious and uncertain legal quandary. For decades, the social pressure to emulate eurocentric hair has permeated American society, especially influencing Black women’s hair and their grooming decisions. Despite this, some Black women have continued to stand their ground and maintain their unique hairstyles regardless of the mounting pressure that they receive from society.

Danielle Twum, a scientist with a Ph.D. in Cancer Immunology, said she has experienced microaggressions because of her natural hair.

“While I was pursuing my Ph.D., an incident occurred in the bathroom with one of my professors,” she said. “I had on a crochet hairstyle, and I ran into her in the bathroom and after seeing my hair, she asked me how I could afford to do my hair, and change the styles regularly with the little graduate stipend they were paying me.”

Although Twum, like many other Black women, is aware of the prejudices that surround Black women and their hairstyles, she doesn’t allow it to define her.

“To me, hair is a fun way to express myself,” she said. “It’s a portion of me, but it is not entirely me. I am aware that as a Black woman, there are a lot of stereotypes surrounding my Blackness, but there was a reason I got a Ph.D. It was so that there wouldn’t be any doors closed to me.”