A glimpse of something approaching normalcy faded from classrooms as quickly as it appeared when the Omicron variant of Covid-19 first arrived in the US in the beginning of December. The hope that winter break would provide an opportunity for viral spread to slow and schools to reassess safety strategies proved in many places to be a pipe dream.

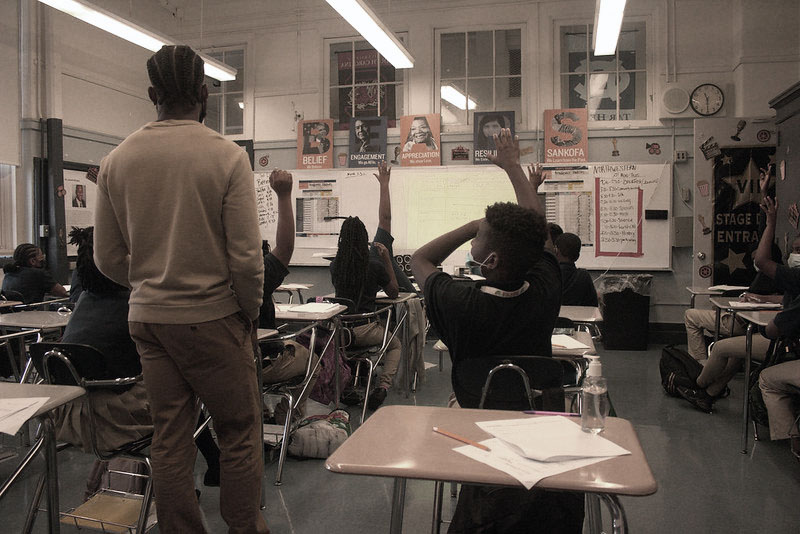

Deyshawn Clarke, a Brooklyn mathematics teacher in the Uncommon Schools Charter network, had one word to describe his school’s return from winter break: Bananas.

“A lot of our teachers had it during break, and a lot had it even two or three weeks ago when we were first coming back,” said Clarke. “We only had about 40 (of roughly 250 overall) students in person that first week back because parents were either afraid to send them to school or they already had Covid and were quarantining.”

Between covering classes, contact tracing students, and beginning to prepare students for state testing, Clarke feels torn between safety and believing in-person learning is most beneficial for everyone involved. In accordance with new shortened quarantine guidance from the CDC, some of Clarke’s colleague’s returned to work while still positive with Covid.

“The guidance is constantly changing, people are confused and frustrated, it’s a lot to keep up with. We’re doing a good job staying positive, but it’s definitely been exhausting,” said Clarke.

Dr. Jen Jennings, a professor and education researcher at Princeton’s School of Public & International Affairs, utilized New York State’s Covid Report Card to gauge the severity of Omicron’s impact in New York City through the first three weeks of the new year. Her analyses revealed that between January 4 and 21, 18.1% of staff contracted Covid-19 – three times the New York City’s rate of infection in the general population.

🧵1. NYCDOE Schools COVID Update

Let's take stock for this month

⚠️10.5% kids & 18.1% staff infected btw Jan 4-21➡️Kids rate = 1.75x NYC rate (which was 6%)

➡️Staff rate= 3x NYC rate— Dr. Jen Jennings (@eduwonkette_jen) January 24, 2022

While increased testing prompted by new Mayor Eric Adam’s aim to bolster the ‘nation’s largest in-school surveillance program’ provides context for the prevalence of viral spread, it does little to mitigate future infection.

“It’s a surveillance measure, it provides a sense of what the data look like. But it’s not a mitigation measure, it’s not going to get very far in terms of actually, you know, identifying and quickly isolating cases before they spread,” said Jennings.

A Box fan with filters duct taped to the sides was provided to special education teacher Stacy Barrantes to help circulate air in her classroom. Photo courtesy of Stacy Barrantes

While no setting has been spared, under-resourced schools have borne the brunt of Omicron’s spread with less at their disposal to effectively combat it. Stacy Barrantes, a first year special education teacher at a Northern New Jersey public school, has felt keeping her kids safe has been largely up to her.

“The first day we got back from break I found a big fan with, like, a bunch of filters attached to it in my room that was supposed to help us circulate air in our rooms, which was crazy,” she said. “A lot of teachers are mad. A lot of the attitude among staff, like anyone you talk to, has been let’s just get to Christmas, let’s just get through the week. You could feel the stress of who’s going to have to quarantine next?”

Even though Barrantes’ school offered an option for remote learning the first week after winter break, four students chose to return in person while still positive with Covid. One of her colleagues broke down in tears confiding in her about how disrespected and daunted the task at hand seems.

“It’s like a lose-lose situation for us right now,” Barrantes said. “Everybody wants and expects different things and we’re trying our best – I’m a team player and am trying to help out however I can. But it’s been scary for sure and exhausting trying to keep everyone safe and happy.”