When Bonnie Campbell arrived in Washington as the first director of the Violence Against Women Office in 1995, she encountered a government determined to implement the first federal legislation to address domestic violence.

Her time directing the office established by the Violence Against Women Act constitutes some of her proudest memories. Now it’s also a painful reminder.

“What we’re seeing now is just all the more abhorrent to me,” Campbell said. “It’s hard to believe what’s happening.”

Although a bipartisan coalition passed the original act, reauthorization efforts have disintegrated into accusations of election politicking by both parties. That divide has put on hold more than $650 million of funding for programs that address domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault and stalking. Now proponents like Campbell wait for elections to determine the fate of the bill.

“It’s a disturbing time across the country,” she said. “If I didn’t have a background in politics, I wouldn’t understand it myself. I tell you, it makes me crazy.”

Renewal of the legislation stalled after conflicting bills emerged from the two chambers of Congress. On April 26, the Senate approved a reauthorization bill with the support of all Democrats and about one third of the Republicans. Key provisions included language to protect individuals regardless of sexual orientation, to extend tribal jurisdiction to domestic violence cases perpetrated by non-Indians against native women, and to increase the number of temporary visas for immigrants who are the victims of domestic violence.

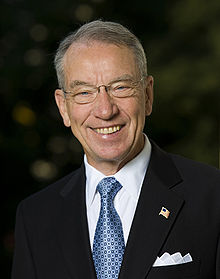

Chuck Grassley, the ranking Republican on the Senate Judiciary panel, said he voted against the bill due to “significant waste, ineligible expenditures, immigration fraud and possible unconstitutional provisions.”

The next day, the House of Representatives introduced a narrower reauthorization bill stripped of those provisions. It passed by a slim margin of 222-205, with the support of just six out of 190 Democrats. The House bill included harsher sentencing requirements for stalkers who target children and the elderly and increased funding designated for testing rape kits.

Jenny Rivera, a law professor at the City University of New York, is frustration at the politicization of the bill.

Jenny Rivera, a law professor at the City University of New York, expressed frustration at the politicization of a bill that had drawn bipartisan support for the past 18 years.

“These things are contentious, and I’m not saying there haven’t been challenges at other times,” she said. “But the reality is that, given the culture in Congress, … this is the most contentious I’ve ever seen the bill.”

John Conyers, the top Democrat on the House Judiciary committee, is among many who say that Republicans are blocking the bill due to its provisions for same-sex couples, immigrants and native women.

“We want every member of the House Judiciary Committee to realize that this attack on women is going to be noted across the United States of America,” he said, during a press conference.

Many others, such as Sen. Jeff Sessions, have accused Democrats of using the Senate bill in order to be able to accuse Republicans of being anti-women.

“You think they might have put things in there we couldn’t support, that maybe then they could accuse you of not being supportive of fighting violence against women?” he told The New York Times.

The voting records support a strong bipartisan history beginning in 1994, when the legislation passed unanimously in the House as part of an omnibus crime bill. Campbell, who was then the state attorney general of Iowa, recalled support among other groups as well.

“I was working with state attorneys general, and some were pretty conservative and others were pretty liberal but no one was disagreeing over whether this legislation needed to pass,” she said. “It was significant because typically state attorneys don’t like when the federal government enters into their domain of criminal justice. But everyone understood that, if you’re a batterer or rapist crossing state lines, we’re able to get there.”

The legislation also established the Violence Against Women Office, which Campbell was appointed to run by then President Bill Clinton. The office, which has since been renamed the Office of Violence Against Women, administers financial and technical assistance to programs and policies established under the Violence Against Women Act.

The office has awarded more than $4.7 billion in grants and cooperative agreements. Funding has responded to expansions in the legislation to include sexual assault and stalking and different underserved populations.

In the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000, the reauthorization extended protections to battered immigrants, sexual assault survivors, elderly victims, victims with disabilities and victims of dating violence.

John Cooksey, a Republican former representative, co-sponsored the bill.

“I feel more strongly about this because I have three daughters, now seven granddaughters,” he said. “But everyone realized that there are some bad guys out there that abuse women. There was no controversy over what should be done.”

The act was reauthorized a second time under the Violence Against Women and Department of Justice Reauthorization Act of 2005, which passed the House with a vote of 415-4. The bill focused on increasing access to services for racial minority groups, immigrant women, youth victims and tribal and native communities.

Rivera, the CUNY professor, said that the changes in the bill have been incremental responses to the needs of different populations. She believes that this remains the case with the legislation pending in Congress.

“Really, the reauthorizations raised the opportunity to think about what had gone on and for academics and policymakers to evaluate the impact of statute and how we can do better,” she said. “There are always issues that we didn’t anticipate, and we had a chance to address.”

Campbell worries that the climate of partisan hostility marks a trend that threatens to extend beyond the election. She has been troubled by what she identifies as a backlash against the legislation and the growing polarization over women’s issues.

“What has changed is the outspokenness of opposition,” she said. “The political environment has changed dramatically regarding the acceptance of radical views. Not just on domestic and sexual violence, but about abortion, contraception and pay equity.”

The bill remains in limbo. Rivera wondered whether it may pass in a lame-duck session. Campbell is certain the election will determine much more than when the bill is finally reauthorized.

“We know nothing will happen until after the election,” she said. “But then what?”