SOUTHEAST ASIA’S OBESSION WITH FAIR SKIN STORIFY

At Muskan Beauty Parlor in Journal Square, N.J., women come to be made pretty.

The shop – nestled in the South Asian enclave dubbed India Square – greets customers with melodies from classic Bollywood films while women get their hair styled, eyebrows threaded and nails manicured.

Salon manager Hira Farruk said skin-lightening treatments are also popular with Indian and Pakistani women who predominantly make up their South Asian clientele. Here, as in many South Asian communities, being pretty sometimes means having fair skin.

But 31-year-old Indian American Naheeda Sayeeduddin of Houston said people outside of South Asian circles never judged her because of her skin color. Nobody has ever asked her why she’s not lighter.

In fact, the South Asian community’s deep-rooted fixation with fair skin seems to be fading as immigrants’ first-generation American children have become less color-conscious than the countries their families hail from.

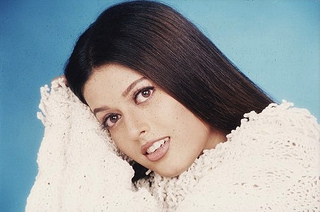

Naheeda Sayeeduddin, 31, wanted to be fair-skinned as a teenager. “All I ever saw were these fair-skinned actresses,” she said of Bollywood, India’s multibillion dollar movie industry. Photo by Brian Styles.

“Today, they don’t care because they’re not exposed to that discrimination that’s in India,” said Sayeeduddin. “Maybe some girls haven’t been there, or if they have, they know that [skin color is] not important.”

But Sayeeduddin, who used to watch Bollywood movies as a teenager, wanted to be fair-skinned once. Most of the actresses who appear on Bollywood’s silver screen have light skin, light hair and light eyes – the country’s ideal standard of beauty even if it’s in striking contrast to medium to deep brown tones of the average Indian woman.

“All I ever saw were these fair-skinned actresses,” said Sayeeduddin. “I thought that’s how girls are supposed to be.”

When she was 16, she began using Fair & Lovely, India’s most popular fairness cream, which claims to take care of a myriad of skin imperfections, such as dark patches, dullness and suntans. But Fair & Lovely’s main selling point is its promise to make skin fairer.

“It’s ingrained in the culture,” said Azra Rezwi, a retired plastic surgeon from India now living in the Upper East Side, Manhattan. “It is the social norm.”

![I went to a school [in India] where there were a lot of English girls, and I never thought I wasn’t as good as anybody," said 70-year-old Azra Rezwi, a retired plastic surgeon from India now living in the Upper East Side, Manhattan. Photo by Zahra Ahmed.](https://pavementpieces.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/lady.jpg)

I went to a school [in India] where there were a lot of English girls, and I never thought I wasn’t as good as anybody,” said 70-year-old Azra Rezwi, a retired plastic surgeon from India now living in the Upper East Side, Manhattan. Photo by Zahra Ahmed.

Rezwi, 70, has been retired from her private practice in Manhattan for almost 10 years, but said patients came to her in search of creams or treatments that could give them fair skin.

“When I was growing up in India, I never saw this,” said Rezwi of skin lightening. “But it’s very common now that there are several brands of creams and treatments to make skin lighter.”

India’s skin-lightening creams made up a $432 million market in 2010, which is currently growing at 18 percent every year, according to market researchers ACNielsen. One of India’s most popular male actors Shah Rukh Khan can even be seen in an advertisement tossing a tube of Emami Fair and Handsome – a fairness cream tailored to men’s needs – to a dejected, dusky-skinned young man in a swarm of Khan’s fans. The product’s tagline is that it’s for men who want “zyada,” or “more,” long-lasting fairness.

But to Rezwi, Khan’s endorsement of a fairness cream is “silly,” especially because the actor has medium brown skin himself.

“I have normal Indian brown skin,” she said. I went to a school [in India] where there were a lot of English girls, and I never thought I wasn’t as good as anybody. Thank god I didn’t have that complex.”

Still, Rezwi admits that South Asians, especially immigrants, are “very color conscious,” but it’s “not important for girls of [South Asian] origin who are growing up here.”

Asma Ahmed, 29, who was born in Hyderabad, India and grew up in Austin, Texas, often struggled with her deep brown skin as a teenager. Ahmed said she used Fair & Lovely in high school to make her skin lighter. It was particularly tough during visits to see her relatives in India.

“I was surrounded by many people who thought dark skin was really beautiful,” said 29-year-old Asma Ahmed of Austin, Texas. “It was so different from them that they thought it was fascinating.”

“At a very young age, I remember hearing aunts talk about other girls,” she said. “Very often the words were ‘She’s really pretty. She’s really gauri (fair).’ Gauri in the same sentence as pretty…it doesn’t take much to ingrain that into a kid’s mind.”

Ahmed, who had light-skinned friends in high school, grew to eventually accept her skin over the years.

“I was surrounded by many people who thought dark skin was really beautiful,” said Ahmed. “It was so different from them that they thought it was fascinating.”

Her mother, who always stressed that beauty depends on a person’s character and how they nourish their body, also played a major role in Ahmed’s acceptance of her skin color.

“It means a lot to me that my mom – even being light-skinned – sees me as beautiful in my own skin,” she said. “It’s important to remind your daughters, your friends and yourself that beauty doesn’t come from the outside.”

Ahmed said that was a powerful message every South Asian mom should communicate to her daughter.

Munireh Sayed, 34, a former local model from Mumbai, India who now lives in Pennsylvania, is naturally fair-skinned and said she and her mother used Fair and Lovely to protect against uneven sun tanning back in India.

Munireh Sayed, 34, a former local model from Mumbai, India who now lives in Pennsylvania, said America is “more progressive” when it comes to skin color. Photo by Daboo Ratini.

Sayed said though her mother used the cream, she was always open-minded about skin color.

“[My mom] would say it doesn’t matter what color you are from the outside because you have to be good from the inside too,” she said.

Sayed said she now gets questions from her kid daughter, who has a wheatish skin color, about how her mom turned out to be fair-skinned.

“I keep telling her it doesn’t matter,” said Sayed. “I feel sorry for young girls who are pressurized to use all these products and to constantly feel like they are not worth something in life because they’re not fair.”

But even in India, Bollywood’s women are taking a stand on the issue. Actress and director Nandita Das, who has always been outspoken about the issue of skin color, has often said that India’s fairness obsession goes back to the caste, or social class, system and culture.

Das now supports a campaign called Dark is Beautiful, which according to its Facebook page raises awareness about the unfair bias towards fair skin in India and celebrates beauty and diversity of all skin tones.

Her advice to women with South Asian heritage: “Focus on your interests and talents and do things that make you happy instead of making your looks the focal point of your identity. Let your attitude and behavior define you and not just whatever you are born with.”

Still, India has been slow to the shift in color-consciousness. Ahmed visited a few weeks ago and said she saw many ads and billboards with fair-skinned models, some even with white women.

“I think there’s a subliminal message there,” she said. “That light-skinned is better.”

But Ahmed said South Asian Americans are beginning to care less about skin color partly because of campaigns like Dark is Beautiful and the impact of social media.

“I’m a strong believer in celebrating women for their natural beauty,” said Ahmed. “The age of the internet and the age of media that’s able to spread the word really brings to light this ugly phenomenon with the obsession of light skin.”

In fact, social media did just that earlier this year when Nina Davuluri, a New Yorker of Indian descent, received backlash after winning Miss America 2014.

While Davuluri was breaking barriers in America as the second Asian American winner and first Indian American winner, many twitter users said the newly-crowned Miss America was “too dark” to ever win a pageant in India.

For Rezwi, the comments were ironic.

“In America, they see you on your overall ability and poise,” she said. “In India, you have to be light-skinned.”

While Davuluri is the first Miss America of Indian heritage, she’s not the first to win a major pageant title. Miss Universe and Miss World have had two and three Indian-born winners respectively.

Sayeeduddin, like other South Asian American women, found people more accepting of her skin color in the U.S.

“I think that’s helped me become a lot more comfortable,” she said.

Ahmed even cited women of African origin as a source of inspiration.

“I love when I see very dark-skinned Kenyan women or African women who are in the spot light,” she said. “Those women are sometimes much more darker than women in India, but to see that they’re recognized for their beauty and contribution is such a gratifying thing.”

Rezwi said other Americans find dark skin more exotic. But years ago at her practice in the Upper East Side, women of all nationalities would ask about skin-lightening treatments and products. She said she advised them only if they had abnormal pigmentation, but did not encourage them to change their skin color.

According to Rezwi, hydroquinone – a skin-bleaching ingredient found in some fairness creams – is harmful to skin, preventing the function of melanin, and the FDA approves only a 1.5 to 2 percent concentration of the ingredient.

“The higher concentration, the more potent it is,” said Rezwi. “These people unwittingly use more concentrated forms and this can give to complications.”

Complications include white patches on the face and even the opposite effect of skin becoming dark because lightening treatments reduce melanin protection.

While Fair and Lovely doesn’t contain hydroquinone, its lightening effects last only several weeks before skin returns to its natural shade. To maintain fairness, the product must be used regularly.

“I gave up because I didn’t see [the cream] doing anything for me,” said Sayeeduddin, who stopped using the cream in her later teenage years. “It wasn’t working.”

While India’s fairness cream industry doesn’t seem to be slowing down any time soon, many women with South Asian roots have found America to be more welcoming of various brown skin tones.

“You accept the fact that beauty is skin deep,” said Sayeeduddin. “It’s not only on the surface.”

Comments

[…] Published on Pavement Pieces. […]