Except for “ready” and “done,” “fuckin’” and “shit” are the two most used words on Neptune, a hand-crafted 50-year-old boat that docks at Cape May, NJ. Anthony Mattia, 41, the captain, curses the most often.

That owes to his “dysfunctional personality,” Mattia said. It’s a condition caused by the immense pressure he undergoes.

For many years, Mattia has driven into the empty dark-green ocean, knowing each new day will be a replica of every previous one: drive to the spot; set the catching pots; light another Pall Mall. Foot on the ground, Mattia brings his crop to his dealer and leaves with several barrels of baits to prepare for the next sail.

He lights another Pall Mall, before finally heading home.

In the 21st century, where people surf the internet and drive cars, fishing, a skill that was once needed for the survival of mankind, has faded into the background and been replaced. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of registered individual commercial fishermen has declined by about 40 percent over the past two decades. The average annual income is approximately $30,000, at around minimum wage.

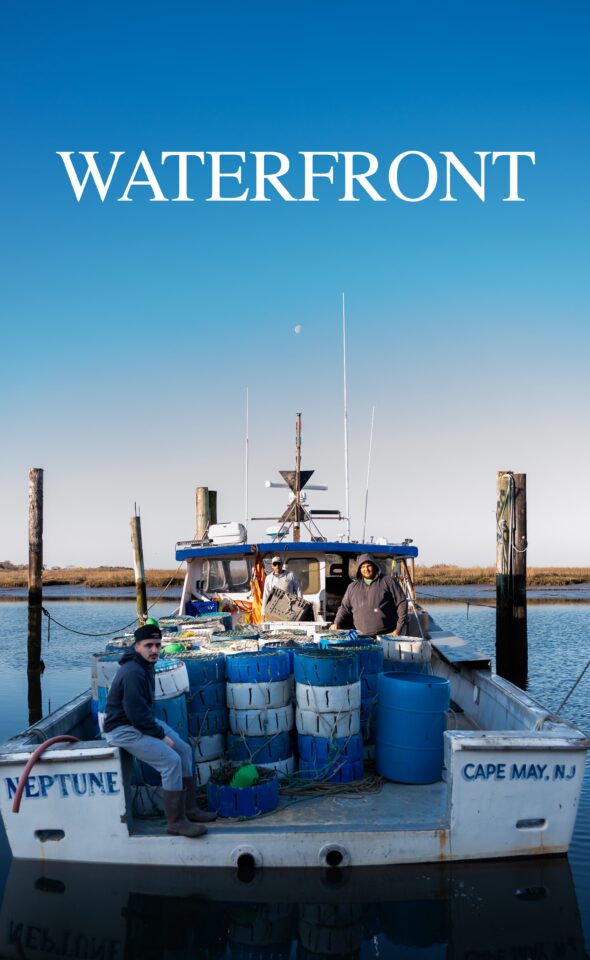

Anthony Mattia (left) with his family on the boat. Mattia’s fingers are tattooed with his daughters’ names, Mira and Isla. (Photography by Simon Tan.)

The water ebbs and flows. The people come and go.

Widely remarked as one of the most physically demanding jobs, fishing also ranks second place in fatality rate, almost 30 times higher than the average. According to BLS, each year, the approximately 39,000 commercial fishermen lose 44 of their fellows.

As a trade that is friendly to novices — a few days on the crew will make an okay deckhand — the fishing industry invites some immature minds that treat this job like a gold rush.

For most, they get on the boat and work as deckhands for a few sails. After leaving with the money, they never come back.

Mattia frequently finds deckhands struggling with addictions and alcoholism. It’s not easy to find people that truly take fishing as their career, he said.

But Frank Wehmüller is different. He does not smoke; he’s not on drugs; he’s not a client of the sex workers. He started as a deckhand and made his own catching pots and bought his own boat.

“Frankie’s a rare find,” Mattia said.

Three years ago, when he was exploring different jobs after dropping out of college, Wehmüller accepted an offer to work on a headboat. Ever since then, he couldn’t get off the boats.

“It’s freedom,” he said. “I love the water.”

Frank Wehmüller on the boat. He was an apprentice to Mattia and now he owns a smaller boat. (Photography by Simon Tan.)

After Mattia drives the boat to the spots that are likely to produce good crops, Wehmüller will drop the catching pots into the ocean. The pots, used to trap shellfish, are divided into groups and tied to a buoy. The crew will be back in four to five days to collect the pots. (Photography by Simon Tan.)

If Mattia heard that, he would’ve nodded. Yeah, fishing is what he always likes. It’s the borderless ocean; it’s a 50-year-old boat; it’s the I-am-my-own-boss freedom; it’s …

It’s a lifestyle.

“Of course, these guys (like us) will make good money, but if you average it out – some days you have good days, some days you have real good days, some days you have real bad days,” Mattia said. “It’s not so much we go for the money; we go for a lifestyle. We have freedom.”

Over time, the fishing industry has evolved into what is like a giant family business, in which everyone knows each other. Anthony Mattia’s father, Paul Mattia, is the diesel guy, and his nephew, Christopher Mattia, is an apprentice learning from him and Wehmüller.

Anthony filling up diesel for his boat Neptune. Behind him are (from right) his father, nephew and neighbor.(Photography by Simon Tan.)

Chris Mattia and Wehmüller preparing baits for the next sail. They chop the baits into pieces so that they will fit in the pots. (Photography by Simon Tan.)

But different from other big families who take pride in their legacy and heritage, the fishermen are less sure what they can prepare for the future. Paul wanted Anthony to be an electrician, and Anthony wanted his children to finish the college that he dropped out of some twenty years ago.

Chris also dropped out of college. He now works as a YouTuber, posting videos about NBA2K and Grand Theft Auto for a few hundred, sometimes thousands, views. He wanted to save enough money to buy a car.

When I asked Chris what if fishing turned out to be his life- time job, he hesitated.

Chris Mattia throws the buoy into the ocean. He learns fairly quickly. On the second day, he can do all the things on his own. April 12, 2023. (Photography by Simon Tan.)

“Damn me. Yeah… Never fuckin’ know, you know?” he said.

“You never know.”

Christopher Mattia, Anthony Mattia’s nephew, joined the crew. He is an apprentice to Wehmiller and wants to buy a car with the money earned. April 11, 2023. (Photography by Simon Tan.)