Students working with the Situation Project get a chance to shadow staff at the show. Photo courtesy of the Situation Project.

For many students, after-school theatre club is a place of refuge. They become stage managers and costume designers; they are lead actresses and featured dancers. It’s an activity that lets them relieve stress, form friendships, and can lead to better grades.

But thousands of students across New York State don’t have access to these opportunities. Their schools don’t even have art classrooms, let alone space for a theatre. Budgets can barely cover classroom supplies – costuming and staging a production is out of the question. While arts funding is actually slightly increasing, a lot of New York City students won’t see any changes.

“I constantly bemoan the state of arts in the schools,” said Judy Tate, a professor at New York University. “For as long as I’ve been in arts education, I feel like the resources have been shrinking and shrinking and shrinking.”

Tate is a teaching artist who works with Manhattan Theatre Club. It’s one of many organizations that works to make sure that students across the city get the opportunity to study and practice theatre.

With the help of these organizations, students from schools across the city get the chance to go backstage at best-selling Broadway shows, learn from professional actors, and bring theatre into the classroom.

A Neighborhood-Specific Crisis

While arts funding is slowly improving, the majority of schools are still at a disadvantage, especially in lower-income neighborhoods.

“People want to come to school when they’re going to stay for the after-school drama club, or when they’re going to play music,” said Tate. “Arts is one of the things that helps people stay in school, and that people in charge don’t recognize that – it’s really disheartening.”

While the amount of hours mandated varies based on grade, the state requires that students spend between 93 hours and 186 hours per academic year on arts education, taught by a certified arts teacher. High school students must complete a certain amount of arts education hours to graduate – at least on paper.

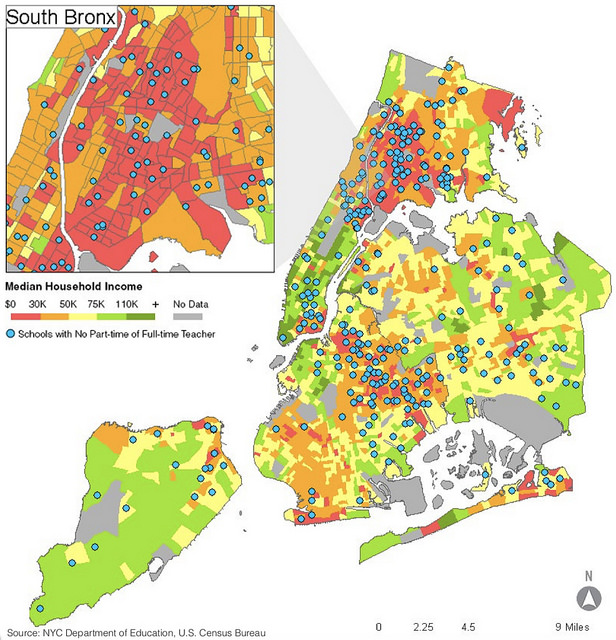

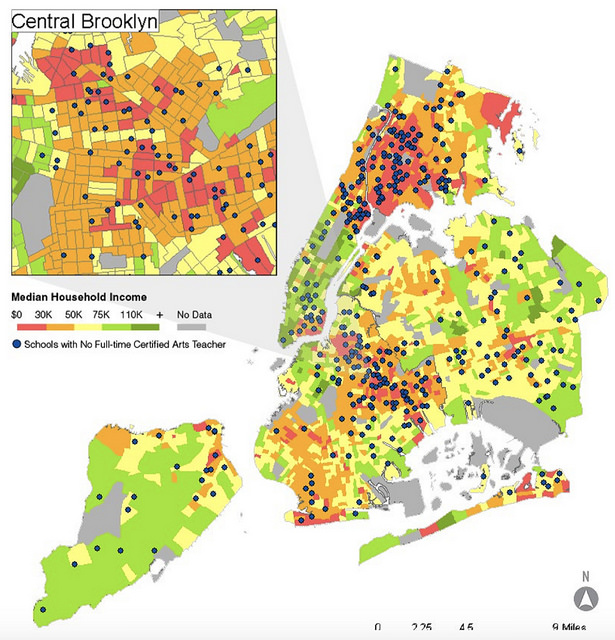

But according to a 2014 report released by the office of the city comptroller, 28 percent of schools in New York City do not have a full-time certified arts teacher, while an additional 20 percent of schools have neither a full- nor part-time certified arts teacher. More than 42 percent of schools without these teachers are located in the South Bronx and Central Brooklyn, despite these neighborhoods only having 31 percent of all NYC schools.

The above charts, taken from the NYC Department of Education, show median household income compared to the amount of arts teachers in the districts. Right: schools with no part-time or full-time certified arts teacher, focusing on the South Bronx. Left: schools with no full-time certified arts teacher, focusing on Central Brooklyn.

The above charts, taken from the NYC Department of Education, show median household income compared to the amount of arts teachers in the districts. Right: schools with no part-time or full-time certified arts teacher, focusing on the South Bronx. Left: schools with no full-time certified arts teacher, focusing on Central Brooklyn.

“There are instances, significant instances, of inequity, studies showing there’s a kind of correlation between high poverty areas and low arts in schools,” said David Shookhoff, Director of Education at Manhattan Theatre Club,. “There are problems, and we’re trying to adjust those problems.”

Filling the Gap

In the neighborhoods where these gaps exist, there’s no theaters or concert halls, not even off-off-off-Broadway spaces. There’s hardly any museums, and no art galleries. Instead, streets are lined with fast food restaurants, convenience stores and small businesses. As a result, many students don’t even have the chance to consider a career in the arts, let alone work towards one.

That deficit can be seen at The Academy of Applied Mathematics and Technology, or MS-343. Located in the Bronx, it’s among the schools that have no full- or part-time arts teachers, and while it’s highly ranked, according to the city’s Department of Education’s performance dashboard, it is located in one of the poorest Congressional districts in the country. In 2011, they were approached by Damian Bazadona, founder of the Situation Project.

“The school was missing something critical,” said Bazadona, “access to the extraordinary arts and cultural offerings of their city.”

Bazadona worked with MS-343 principal to secure 300 tickets to the then-running Spider-man: Turn Off the Dark. According to Bazadona, it was the first time many students had been on a field trip, let alone seen a Broadway show.

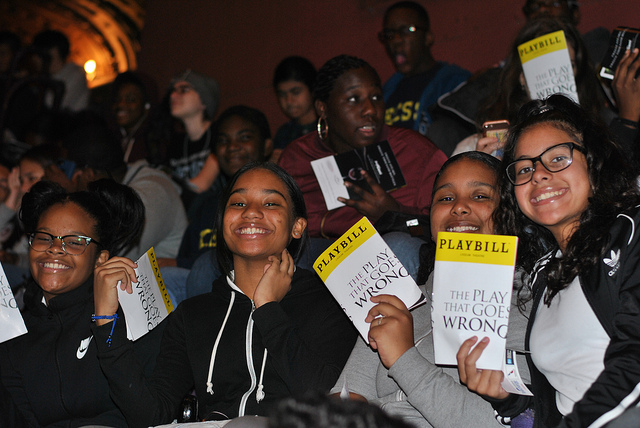

“Knowing what theatre meant to me as a young person, I think we have a responsibility to share our work with as many young people as we can,” said Seth Greenleaf, a producer at The Play That Goes Wrong, which the Situation Project recently brought students to. “Especially those without the means to attend on their own.”

The program has grown to include employee shadowing, artist talkbacks, on-site education seminars, and multiple shows. By the time a student whose school is involved with the Situation Project has graduated middle school, they’ve seen half a dozen shows.

“The biggest benefit our students have had is the opportunity to expand their cultural lens while also being given the chance to appreciate the arts,” said Tania Sanchez, an assistant principal at PS/MS 278, via an email with Bazadona. “Students have also made a personal and real connection to the performing arts especially through the opportunities to meet the cast and ask questions.”

The Situation Program can’t bring the arts directly into the classroom, but it makes sure that students at least have the chance to experience live theatre, and see the potential career paths ahead of them.

Meanwhile, Manhattan Theatre Club gives students a chance to write their own plays and see them staged by professional actors. MTC’s teaching artists also work alongside classroom teachers, blending theatre education with the existing curriculum.

In the past year, MTC has gone into 50 schools, working alongside 83 classroom teachers and impacting the lives of nearly 3,000 students.

“The work is designed as a collaboration between classroom artists and classroom teachers,” said Shookhoff. “Ideally, and i think in most cases in reality, the teacher and the teaching artist plan the work that’s going to take place in the classrooms, and collaborate in the classroom, and the expectation is that the classroom teacher is going to carry the work forward.”

The classroom work can include anything from learning about and preparing to see a play, learning how to write and stage plays of their own, and having the chance to see their work performed by professional actors. While MTC offers multiple programs, they all have a similar mission: ensuring that students across the city get a chance at a quality arts education.

“The idea is to bring [students] in contact with the power of live theatre, as a way to help them understand themselves and the world,” said Shookhoff. “What we’re doing is filling a gap. We’re making up a deficit.”

Arts Leading to Increased Outcomes

Arts education leads to increased outcomes – but not just in academic terms. Students who are exposed to arts are more likely to go to college, to be civically engaged, and be better off socially.

“The crazy thing is, if you put [resources] into the arts, kids will tend to stay in school,” said Tate, who went on to explain that she has seen students become interested in, and eventually go to, colleges due to the increased opportunities for theatre there.

Bazadona said that in addition to seeing an increase in students wanting to go to college, many of them were specifically looking at performing arts schools.

“Before Situation Project, the number of kids in our founding school [MS-343] who applied to performing arts schools was about zero to two, out of a class of 100,” he said. “By the time the first Situation Project class was ready to graduate, 16 students had applied.”

Students involved with the Situation Project attended a performance of The Play That Goes Wrong. Photo courtesy of the Situation Project.

Both organizations agreed that while they don’t exist deliberately to lead students into theatrical careers, letting them see the potential careers that lie ahead of them is always a benefit.

“Our mission is not audience development, or talent development, per se,” said Shookhoff. “It’s about expressing aspects of humanity. That’s what we want our students to do, by coming to see our plays and preparing to see the plays. The plays that we ask them to write ultimately are ways for them to express what’s on their minds and in their hearts.”

Shookhoff explained that it’s also easy to see the changes in students in just a few weeks, both as they write their own plays and see live shows performed.

“The kids are excited about what they see and what they’ve done,” he said. “When the lights go down at the end of the play, there’s a palpable enthusiasm in the audience. They really dig the work, and connect with it. It becomes, in some cases, an almost rock-concert sort of enthusiasm.”

Always Hoping to be of Use

While arts education is still almost nonexistent in some parts of New York, there are indications that it’s getting better. This year, the National Endowment for the Arts, which President Donald Trump has frequently threatened to cut, actually saw an increase in its funding. City mayor Bill de Blasio has increased the amount of funding that goes towards arts education.

“The trend is positive,” said Shookhoff. “There’s been an effort to rectify a deficit situation. The hole is so deep that it certainly hasn’t been completely filled, but they’re trying.”

The increases will inevitably help students across the city. However, even if the situation continues to improve, these organizations still hope to be involved in bringing theatre to students.

“Even if all the schools were in compliance with state mandates for art education, which they’re not, there would still be a role for organizations like MTC,” said Shookhoff. “We are the professionals, if you will. No matter how great your theatre program is, without the existence of Manhattan Theatre Club, you’re not going to see world class productions of plays by August Wilson or Sam Shephard. We’re always, all of the organizations, a value add.”