Ever since Melissa Barber was a six-year-old girl living in the Bronx, she knew that the air wasn’t clean — she could feel it on her skin and when she breathed.

The South Bronx native said she could tell the difference when she went to other boroughs and realized that it was negatively affecting the health of those around her.

“The way they take care of another neighborhood is different than how they take care of my neighborhood,” Barber would say when visiting other communities. “The pollution or garbage that I see on the street is different from what I see here in my neighborhood. You begin to see who is perceived as valuable and who isn’t.”

The author, community organizer and activist also said the congested traffic in the Bronx has always been harmful because of all the trucks that pass through and release toxins into the air. When her daughter was younger, she would get allergies due to the dust in the air and recalls being scared of a wheezing noise she would often make.

Barber said she knows way too many people who find it hard to breathe the Bronx air or who live with asthma as a result. An anticipated congestion toll plan would make matters worse for her and her daughter, especially living near the Hunts Point waterfront.

While Midtown Manhattan is expected to benefit from congestion pricing, the Bronx would potentially be negatively impacted — a lower-income and predominantly minority community of more than 1.4 million residents.

When Mark Naison, a Bronx resident and professor of history and African and American studies at Fordham University, first heard of the congestion toll plan, he was immediately infuriated by the negative impact it could have on his area.

“This is the most outrageous example of cruel and ultimately racially targeted city planning that I have ever heard of,” Naison said. “It’s adding more burdens on people who are already overwhelmingly burdened by tons of discriminatory urban policy.”

Naison says the congestion toll plan’s potential negative effects classify as a crime against humanity.

“The Bronx is where the city puts everything that middle class and upper middle class and wealthy communities don’t want,” Naison said. “They want to save lower Manhattan from pollution by adding it to the Bronx. This is New York City history for the last 60 years — when you have something that the wealthy people don’t want, you put it in the Bronx.”

New York City’s long-discussed congestion pricing program would charge drivers extra to enter Manhattan’s Central Business District or any area south of 60th Street. The MTA is currently assessing what effects would occur.

The MTA’s Environmental Assessment released earlier this August revealed that Bronx residents and environmental justice advocates were concerned about the effects on traffic, air quality and noise in the Bronx as a result of congestion pricing.

The MTA and the Mayor’s Office declined to comment regarding the potential effects as a result of the congestion toll plan.

“We never get to the point where the government does research about the real health effects of what is being done with the pollution,” Barber said. “If you knew what did happen and the detrimental effects, people would probably be suing left and right for what they allow to happen.”

Many Bronx residents like Barber are also expressing concern.

“Participants also commented that the project would affect local traffic volumes and potentially air quality and noise, in environmental justice neighborhoods including … the South Bronx,” according to the MTA’s Environmental Assessment.

The environmental assessment also said members of the Environmental Justice Technical Advisory Group for the plan requested additional information on the potential to increase the number of trucks on highways outside the Manhattan Central Business District (CBD), especially on the Cross Bronx Expressway in the South Bronx. This could happen as a result of congestion pricing.

“Traffic modeling for the project indicates that the CBD Tolling Alternative would result in some traffic diversions around Manhattan, into the Bronx and northern New Jersey and Staten Island in all tolling scenarios,” according to the assessment.

This means the plan could potentially divert diesel truck traffic from Manhattan to the Bronx.

The assessment showed not a single tolling scenario that would produce either a beneficial or neutral impact on congestion on the Cross Bronx Expressway. There were seven scenarios in total.

Representative Ritchie Torres was a strong supporter of congestion pricing up until the environmental assessment was released.

“The Bronx cannot and will not be a sacrificial lamb on the altar of the Central Business District,” Torres said in a public comment.

Environmental hazards are something that isn’t new to Bronx residents. The Bronx is already seen as a vulnerable community due to the burden of pollution and traffic, resulting in high asthma rates. Many residents, activists and leaders have complained about dirty air and ongoing injustice.

“We need real investments that offer a clean and green break from the environmental racism of the past,” Torres said in the public comment. “We need congestion pricing to be not part of the problem, but instead part of a solution that finally brings breathable air to the Bronx.”

Like Torres, many experts believe the plan is racially targeted and are not surprised that negative outcomes would fall on a low-income community of color.

Collection of tweets from South Bronx residents and advocates regarding pollution in the area.

The Bronx is made up of a population that is about 56 percent Hispanic or Latino, 44 percent Black or African American and about nine percent White. The median household income in the Bronx is about $41,000, which falls under the national median household income of about $70,000. About 24 percent of Bronx residents are living in poverty, which compares to the national poverty rate of about 12 percent.

The Bronx also tends to receive a significant amount of traffic due to the four major expressways in the boroughs: the Trans-Manhattan Expressway, the Bruckner Expressway, the Throgs Neck Expressway and the Cross Bronx Expressway.

“There is no place anywhere in the country, if not the world, where you have a neighborhood with 300,000 people surrounded by four expressways with truck traffic,” Naison said, referring specifically to the South Bronx area.

Along with the expressways, the Bronx is also home to several waste transfer stations, where New York City residents can drop off harmful products for disposal. The FreshDirect warehouse and Hunts Point Market are also located in the area, which leads to high truck traffic — a major source of pollution.

Naison says the Bronx is always sacrificed because it is a convenient area for others to put things they don’t want in their own spaces. In the case of congestion pricing, Manhattan wants less congestion. Naison says it’s time to say no and put a stop to the plan.

Similarly, residents unsuccessfully attempted to put a stop to the plan of adding a facility that would produce pollution in the South Bronx area.

South Bronx Unite, an organization with a mission of improving the South Bronx area, campaigned against FreshDirect arguing that the relocation of the warehouse from Long Island City to the South Bronx would further increase air pollution in an already severely-polluted area.

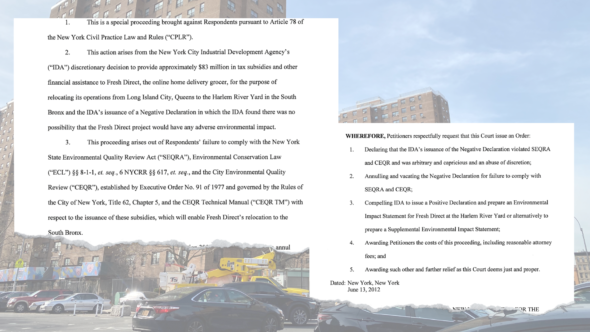

In 2013 when the FreshDirect warehouse was coming to Mott Haven in the Bronx, members of South Bronx Unite filed a lawsuit against New York City and New York State alleging they failed to conduct an adequate environmental review of the site under compliance with the New York State Environmental Quality Review Act.

They instead used a Final Environmental Impact Statement that was prepared 19 years ago for a different project and on a neighborhood that has since been rezoned for mixed-use residential. This specific area of the South Bronx used to be a manufacturing zone with mainly industrial buildings. While there are still signs of industrial activity, the zone is now for residential and commercial use, in which more than 700 residential units have been added, according to the suit.

The plaintiffs viewed this action as “arbitrary and capricious and an abuse of discretion.”

In the lawsuit, the plaintiffs alleged the city “failed to identify environmental impacts” and “failed to account for significant changes to the project and circumstances” since the last review they based the project on. Even without an updated assessment, city officials still decided to provide about $83 million in tax subsidies and other financial assistance to the FreshDirect relocation.

Pages from the lawsuit South Bronx Unite filed against New York City and NY State.

The members of South Bronx Unite also argued that they failed to consider the effects on the area including traffic impacts, greenhouse gas emissions, public health and neighborhood character.

However, the lawsuit and appeal were dismissed and FreshDirect opened its warehouse in 2018. Since the introduction of the warehouse, experts and activists have seen increased traffic, air pollution and noise in the area.

A 2020 study conducted by Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health found an increase in truck and vehicle traffic between 10 and 40 percent since the relocation of FreshDirect. The study found that the introduction of the warehouse especially increased overnight traffic.

Bronx residents whose taxpayer money would benefit FreshDirect were angered at the bad environmental policy that came along with its relocation.

“Having FreshDirect there has had detrimental effects on our environment in that area and it is very dense with so much pollution,” Leslie Vasquez, a clean air program coordinator at South Bronx Unite, said.

Vasquez said FreshDirect also promised they would electrify their vehicles with their implementation in the Bronx. However, they never followed through.

FreshDirect didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment regarding the alleged promise they made and whether they went through with it.

“They didn’t follow their word,” Vasquez said. “The government isn’t really doing anything about it because they don’t care about the Bronx. We still don’t have the electric vehicles that were promised. We have higher carbon dioxide in our air because of so much truck traffic.”

Residents are now fearful of congestion pricing adding to the negative effects of the warehouse that are already causing harm in the area.

The pollution in the Bronx is a silent killer for people with asthma

Bronx’s asthma and pollution rates are at an all-time high and have been for years.

The Bronx has numerous sites that are tied to the ongoing pollution including the FreshDirect warehouse, the Harlem River Yard, Hunts Point Market and Port Morris stations — all largely found in the South Bronx area, which is where the name “asthma alley” comes from.

Bronx air quality is often fair where sensitive groups may experience symptoms from long-term exposure, according to weather services. Current pollutants include nitrogen dioxide, pm 10 and pm 2.5, which are all harmful particulate matter.

According to data released in 2021 by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, the asthma-related emergency department visit rate among Bronx children ages 5 to 17 years was more than two times the rate of all other New York City boroughs combined in 2016.

South Bronx Unite strongly opposes the MTA’s plan for congestion pricing and released a statement condemning the proposal due to every scenario of the plan adding “disproportionately high and adverse effects on traffic, air quality and noise.”

Vasquez moved from the Dominican Republic to the Bronx when she was 12 years old and has lived there ever since. She says the air quality has always been poor.

Vasquez said the Bronx has added a lot of vulnerabilities that make the community even more disadvantaged on top of a lack of quality schooling, language resources and increasing gentrification.

“All of the Bronx’s waste is directed to the South Bronx,” Vasquez said. “The city uses waste management and they direct them to us because we are the least attractive borough and we have so much stigma that our communities aren’t sufficient.”

She said the city tends to view the Bronx as “incompetent” and not deserving of help and quality resources.

South Bronx Unite is in support of the idea of congestion pricing, but they oppose all seven scenarios included in the MTA’s environmental assessment. They believe all scenarios will be “extremely detrimental” to Bronx communities.

“It is very clear that these racial injustices are linked to why there would be less traffic in lower Manhattan and redirected into the South Bronx,” Vasquez said. “We keep being targeted and they’re eliminating this traffic from Manhattan at the expense of the Bronx’s health.”

Patrick McClellan, the director of policy at the New York League of Conservation Voters, an organization with a mission to address environmental justice in order to build healthy communities, says his organization is supportive of congestion pricing but has some concerns regarding equity.

“There is a great potential for congestion pricing to lead to a better public transit system,” McClellan said. “We really believe that public transit is something that needs to be improved in New York City, both from the pollution perspective and from an efficiency and speed perspective.”

He said the NY League of Conservation Voters doesn’t want to see a congestion pricing program that leads to negative impacts on communities that are already dealing with impacts of air quality.

“What we don’t wanna see as a result of congestion pricing is this sort of inadvertent effect where there is more vehicular pollution,” he said.

The organization also believes there are scenarios that will not lead to a negative impact of toxic air on the Bronx.

“We do believe there’s a lot of steps that the MTA, the state and the city in general, can take to prevent any pollution increases and actually even actively lead to pollution decreases in these communities,” McClellan said.

McClellan said air pollution has been linked to increased chronic illness, and Bronx residents fall victim to toxic air that is released living in an area that has a lot of traffic from gas-powered cars, diesel cars and trucks.He said the Bronx is going through a cumulative burden of air quality.

“It’s sort of a toxic soup of different sources and different types of toxic air, and if you breathe that in across your life, you do see that there is an increased rate of asthma, heart disease, other respiratory illnesses and even cancers that do come as a result of this,” he said.

McClellan said that communities of color and communities of low income have been suffering from all of these toxic facilities in the neighborhood, which serves as an example of the way that policies are systemically racist and hurt communities.

He adds that private industries allow municipalities to site toxic facilities in the same neighborhoods repeatedly because it might be cheaper and there might be less public opposition.

“When it comes to congestion pricing, we do support the idea of congestion pricing, but support one that is just and one that is considering equitable equity and the need to address environmental racism at the same,” Mclellan said.

Despite potential negative effects, experts believe congestion pricing will benefit New Yorkers

Some experts and organizations believe that the positives outweigh the negatives and are focusing on the fact that the Bronx may potentially receive these outcomes — it’s not definite.

The Regional Plan Association, a not-for-profit organization that focuses on recommendations to improve the economic health, environmental resiliency and quality of life in the New York metropolitan, has a long history of advocating for the implementation of congestion pricing in New York City.

The RPA was pleased when they heard the news of movement on the plan, according to Rachel Weinberger, Peter W. Herman Chair for transportation at the Regional Plan Association. She said the organization believes the benefits of the program outweigh the potential negative effects.

“We think that until we really start to put the program in, it’ll be unclear what the negatives actually are,” Weinberger said.

The environmental assessment also found mitigation efforts to put in place to try and limit potentially negative effects.

The MTA will prioritize two bus depots that serve environmental justice populations in Upper Manhattan and the South Bronx for the transition of MTA New York City Transit’s bus fleet to zero-emission buses.

The RPA has also mentioned efforts including electrifying the Hunts Point terminal and the trucks accessing it and accelerating plans to cap the Cross Bronx Expressway to a limited number of cars and trucks.

Weinberger believes the MTA should move forward with these mitigation plans regardless of whether congestion pricing gets implemented or not.

“It’s a great opportunity for MTA to do projects that they should do anyway, to clean up the air in the Bronx,” she said. “It would be great to do this project and for those diversions to not materialize, but in either case, you do want to absolutely address any acute crimes that you’re causing to specific communities in favor of benefits for the region.”

Lewis Lehe, an assistant professor in transportation engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, finds it interesting that with congestion pricing, a surprising number of the trips don’t shift to another mode, but they just seem to kind of go away.

He says that the estimated diversions are not set in stone to happen and if following other plans put in place in different cities, drivers have decided to neither take the same route nor divert, but instead take public transportation.

Lehe said that the adaptation of congestion pricing will depend on the geography of the location and also on the specifics of how the system is designed.

“If you get the kind of diversions that the model is saying are possible, then you would have more emissions in the box than you currently have,” she said. “And so that’s why the MTA has to do the mitigations that they’re talking about, which would be moving bus depots and prioritizing the bonds for bus electrification, to combat any of those possibilities.”

However, Weinberger said she remains skeptical of the diversions and doesn’t believe that these outcomes will materialize.

Positive benefits that are likely to materialize include reducing daily vehicle miles, reducing the number of vehicles entering Midtown and creating a source of funding and revenue for the MTA’s public transportation. The plan is expected to provide $15 billion in funding for the MTA.

Most importantly, the plan will reduce traffic congestion in the intended area.

Lehe said there are mainly two motivations for New York City wanting to introduce the congestion toll plan: to repair the transit infrastructure for the revenue side and to lower the number of trips going into the area to reduce demand.

“Traffic and a very dense place like that is really just governed by too many people being in the same place at the same time, so it’s pretty straightforward that it would free up traffic,” Lehe said.

New York City was ranked as the worst among cities in the U.S. in terms of congestion by the 2021 INRIX Global Traffic Scorecard — which doesn’t come as a surprise to residents and commuters in the city

Lehe said congestion toll plans generally create less traffic, which tends to emit loads of pollution.

“Cars emit a lot of pollution when they’re going at like two miles per hour,” he said. “There’ll be less people traveling and also the people that do travel will emit fewer emissions per mile.”

In his work in congestion pricing, he said that the congestion reductions were surprisingly large, even when tolls were pretty small. New York City is thinking of charging anywhere from $9 to $23.

“It seems that there is a certain share of people that just don’t wanna pay anything and they’ll avoid it if they can, even if it’s a small amount,” he said.

Whether New Yorkers pay the toll and go through the area, or avoid it and drive into the Bronx or start taking public transportation, congestion pricing will most likely accomplish its goal of creating less traffic. However, the negative effects and what this means for the Bronx remains uncertain.

“Progress is being made in a sense that the EAA was a milestone and then the hearings afterward, and gathering that and back with the Federal Highway Administration and they’re reviewing it, so it is proceeding according to the protocol and the way that these things work,” Weinberger said.

She said the Federal Highway Administration should have a decision about how to proceed in January of next year. The following steps either include additional analysis or to begin looking for a vendor to implement the congestion toll program.

Barber said the financial impact on Midtown should never take precedence over the health of minority communities.

“With congestion pricing, we need to definitely have things set in place so that there are pools of money for research and so people can actually tap into it because of the health risk and health effects that are happening,” Barber said. “If we’re literally going to make plans to pollute the already poor and already saturated communities, what kind of justice do we have?”