A syringe full of red blood sits on a concrete street barrier underneath an expressway off-ramp near 181st Street and Amsterdam Avenue in Washington Heights. Photo by Razi Syed.

In May 2018, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced four safe injection sites would be built across New York. Nearly a year later, while the opioid crisis rages on, the sites are no closer to reality due to a mix of legal and financial issues and questions about the research that suggests them as a solution.

Not everyone is convinced that the mayor’s office is genuine about wanting to get these sites operational.

“I think they just [announced them] to shut everybody up,” said Axcel Barboza, a syringe exchange and outreach specialist at New York Harm Reduction Educators (NYHRE). “It takes a lot to start a safe injection site up, a lot of money and s–t like that. I think they just said yes to calm everybody down.”

Solutions to the opioid crisis are in high demand as overdose deaths continue to rise across the country. Providing a place to do drugs may sound counter-productive, but according to advocates, these sites they could be the new front lines in the opioid crisis.

“When someone says ‘Oh, I think these things are a bad idea because X,’ I think the thing you need to add onto that sentence is, ‘And that’s why I believe people shooting up in McDonald’s bathrooms is a better thing,’’’ said Peter Davidson, Ph.D., an associate professor at the University of California.

Underneath an expressway off-ramp near 181st Street and Amsterdam Avenue in Washington Heights, used syringes, crack pipes and empty liquor bottles are left lying on the floor in a popular spot for drug use. Photo by Razi Syed.

While SISs do not officially exist in the United States, more than one hundred such sites are operating around the world, including in Canada, Australia, and Europe. They allow drug users to inject themselves in a safe environment, with medical professionals on hand; they provide clean syringes and stock overdose-reversing medications, as well as a place to ‘hang out’ while the high wears off.

Liz Evans has been involved with harm reduction for over two decades. Currently the executive director of NYHRE, she was a co-founder of Insite, a site in Vancouver, Canada, established in 2003 – the first safe injection site in North America. Between 2003 and 2017, three million people injected there.

“[Insite] quickly became so much more than just an injection site,” said Evans. “No one ever died there. Millions of injections have happened there, so for one thing, no one ever dies at an injection site, ever, because there’s staff to make sure you don’t, which is huge.”

According to Evans, these sites are meant to protect those dependent on drugs, while also increasing general public safety in high-risk areas. Research does seem to indicate that they’re doing just that – but there are some who think that the research itself is flawed.

“Many [studies] fail to use an actual control group. They don’t compare the results of safe injection sites to other solutions,” said Alex Titus, a public interest fellow based in Washington, D.C. “The research is sloppy.”

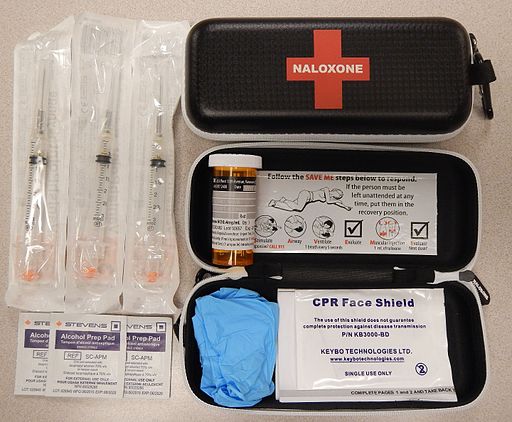

Naloxone, a drug on hand at clinics used to administer in cases of opioid overdose. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia

A significant blow to the safe-injection site discussion came in August, when a major study in the field was retracted. Another analysis, published in the International Journal of Drug Policy, found that the sites have no significant effect on overdose deaths and only a small effect on crime reduction, and found only eight studies that were “rigorous and transparent.”

Magdalena Cerda, DrPH, the Director of the Center on Opioid Epidemiology and Policy at New York University, points out that the research on safe injection sites is mostly preliminary and comes from out of the country, especially from Canada and Australia, where such sites are legal.

Even if safe injection sites can overcome the research-based hurdles they face, they still have to counter legal challenges. In many cities, they are on the brink of reality, including a mock site in San Francisco and an attempted start up in Philadelphia that is currently being challenged by the federal government. Evans thinks that the future of safe injection sites depends on that case.

“The mayor isn’t going to move on it until the governor says it’s okay, and now that there’s this legal case that’s just come up in Philadelphia, I don’t think anyone is going to do anything about it until they hear what the outcome of that case is,” she explained.

The Philadelphia site is being challenged as violating the “Crackhouse Statute,” a law which makes it a felony to “knowingly open, lease, rent, use, or maintain any place for the purpose of manufacturing, distributing, or using any controlled substance.”

Despite these restrictions, there is at least one site operating illegally in an undisclosed location somewhere in the country.

“In about 2013 or 2014, an organization in the United States who provided services to people who use drugs was struggling with the fact that a lot of their service-users were dying of overdose, and they didn’t want to wait,” said Davidson. “They just opened one.”

Davidson performed a research study there, along with Alex Kral, Ph.D., an infectious disease epidemiologist at RTI Health Solutions. The study showed him that safe injection sites are a valid response to the crisis.

“It can be fairly difficult to study something that’s so underground, our research to date has basically said that this facility has saved multiple lives, and doesn’t seem to be having any negative impact on the surrounding community,” he said.

Titus seemed less convinced.

“These sites lead to drug normalization, which is exactly what we’ve been trying to fight,” said Titus. “Advocates claim such sites save lives. Sure, you’re saving that individual that single time they overdose, while continuing to allow them to be slaves to the drug.”

“People are going to shoot up wherever they’re going to shoot up,” said Evans. “That’s a given. This is a response to something that’s already happening.”

Davidson argues that the sites are especially useful when it comes to helping users get into treatment, which can break the cycle of addiction.

Davidson says that while the sites are backed by research, it almost doesn’t matter how effective these sites are – they are always a better option than the alternative.