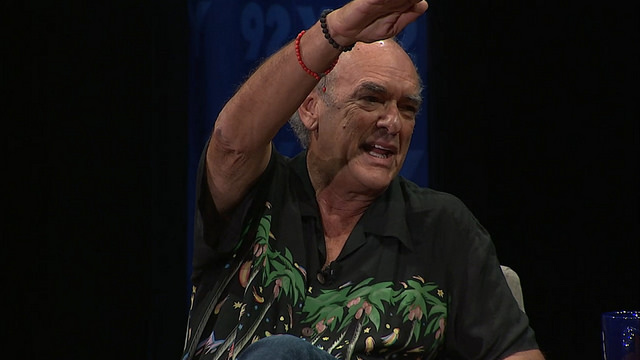

Entertainment industry legend Shep Gordon had many wild stories to tell during his talk at the 92nd Street Y, Thursday night. Photo courtesy of 92nd Street Y.

Picture a world where Emeril Lagasse’s face doesn’t grace the products in the supermarket spice aisle, where there’s no Wolfgang Puck Express in sight at JFK International Airport and where Anthony Bourdain certainly doesn’t have more Twitter followers than Jay-Z. This alternate reality is the one without Shep Gordon, because in the early ‘90s the self-ascribed “food groupie” created a cultural zeitgeist that made the ‘rock star chef’ happen.

Rewind a bit. The first entertainment earthquake Gordon caused was the global mainstreaming of shock rock in the late ‘60s, via his young client Alice Cooper. He also represented Pink Floyd, Anne Murray, Blondie, Teddy Pendergrass and Luther Vandross, later producing Hollywood films.

Bourdain sat down with Gordon last night at the Upper East Side’s 92nd Street Y to discuss his origin, career highlights and transition into trailblazing the new chef marketplace. The event also publicized Gordon’s new memoir, “They Call Me Supermensch: A Backstage Pass to the Amazing Worlds of Film, Food and Rock’n’Roll.” It’s published on Bourdain’s imprint Ecco Press, a subsidiary of Harper Collins.

Within the first four minutes of their talk, Gordon had detailed his – let’s say unconventional – college experience.

“I went to the University of Buffalo. Never took it too seriously… Learned how to play poker. Learned how to deal drugs… I always gave my product to teachers who like it, for grades,” Gordon said.

He told a story about blowing off a summer German class to hang out in Acapulco, Mexico, where he got his product. The class’s professor refused to give him a passing grade, even though it was supposed to be taken care of by a simple exchange of marijuana. So Gordon’s college buddy stepped in and persuaded the professor to give him a C. The friend had leverage because he had previously taken the exam for the professor that the professor was required to pass to earn his doctorate. Gordon laughed hysterically at the absurdity of this story.

After college, Gordon moved to California.

“At this point, had you ever considered transitioning from the pharmaceutical business to entertainment services?” Bourdain asked.

He hadn’t, but he had befriended and was supplying The Chambers Brothers, Jimmy Hendrix and Janis Joplin. Lester Chambers and Jimmy Hendrix told him that, as a Jew who needed a legitimate job as a front for his “pharmaceutical business,” talent management would be the perfect fit. An unknown Alice Cooper was living in the Chamber’s Brother’s basement at the time, so the two were connected.

“And my life in the entertainment business started,” said Gordon.

Fast forward. After achieving a meteoric music industry career, he was with his friend Roger Vergé, one of the most preeminent chefs of his generation, at a gig. It was a million dollar opening of a hotel and Vergé was the centerpiece of the activation. He cooked the meals, gave cooking lessons to the elite guests and promoted the products owned by the hotel – all without getting paid. It had been established chefs needed to do events like this for free to promote themselves and their own restaurants. This mortified Gordon, as did the way the hotel management treated Vergé, “the help.” Gordon’s other friend Wolfgang Puck had it worse.

“I decided I was going to do something, and organize all the chefs into an agency,” Gordon said.

That day in 1992, he did.

Under Gordon, every appearance from a chef came with their name on the marque, as did proper compensation. When the Food Network began in 1993, Gordon negotiated TV deals for his clients where they took reduced upfront compensation for commercial airtime for their products. Emeril’s spice line began this way, making the chef considerably more money than what was possible with a Food Network TV deal. Corporate sponsorships and $100,000 personal chef sessions to the rich came to Gordon’s clients too.

Arielle Dembe, 27, who attended the event, found it interesting when Bourdain then asked Gordon if it’s possible to be happy.

“To me, there’s a subtext to that question because it was announced publicly three days ago that Anthony Bourdain and his wife got divorced,” she said.“He seemed tense and fidgety. I wonder if what’s happening in his personal life had to do with the interview only lasting 50 minutes.”

Despite that, the audience received the two enthusiastically and the night closed with a standing ovation. Gordon grinned broadly on his way off the stage.