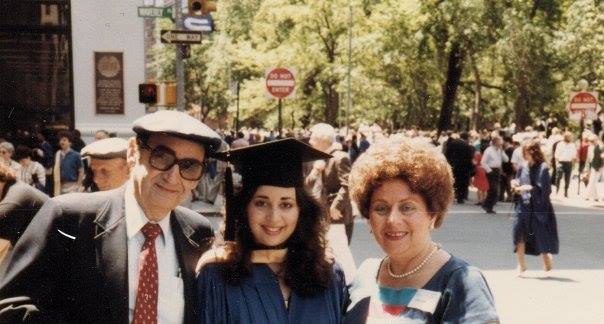

Vivien Orbach Smith with her parents Larry “Lothar” and Ruth Orbach, both natives of Berlin, Germany, at her NYU college graduation. Larry Orbach survived Auschwitz and a death march to Buchenwald.

At first, Vivien Orbach-Smith wasn’t sure she wanted to know the vexing details about what her father, Larry “Lothar” Orbach, had endured during the Holocaust, but in deciding to coauthor his memoir in 1996, she chose to tell the story of one man who survived.

“I became a writer/daughter on a mission: to give voice to the suffering, joys and complex humanity of not only Lothar, but the six million European Jews — 1.5 million of them children — who were killed under systematic, targeted, state-sponsored genocide,” Orbach-Smith said in the foreword of the book, “Young Lothar: An Underground Fugitive in Berlin.”

The NYU journalism adjunct professor and alumna, whose parents are both survivors of the Holocaust, has devoted her life’s work to furthering the stories that surround the tragedy. On the day after Holocaust Remembrance Day, she recalled her father’s life and the legacy of survivors.

“After the war, in the 1950s, the Holocaust was still very fresh,” Orbach-Smith, said. “We were surrounded by physical evidence, meaning the living survivors. Some of them with the numbers still on their arms and thick accents that were evidence of what had occurred.”

But even with visible confirmation of what had occurred surrounding them, Orbach-Smith shared that there was still hesitance to discuss the atrocities to their community.

Vivien Orbach-Smith is the co-author of “Young Lothar: An Underground Fugitive in Nazi Berlin.”

“I was not born into an environment or an American culture where people, Jews or non-Jews, asked questions about the number on my father’s arm or was he in any way encouraged to talk about it,” Orbach-Smith said. “The word ‘Holocaust’ did not even exist. There was no word for what had happened.”

But in recent decades, things took a shift, which many, including Orbach-Smith, attest to the need to tell the stories while they can.

According to the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, the youngest survivors today are said to be 73 years old.

“I think the survivors have more of sense of urgency now that it was time to talk. Before their time ran out,” Orbach-Smith said. “And that they really are the only living witnesses and their testimony would matter.”

NYU students Daniella Panitch and Ari Spitzer may be part of the last generation who will get their education of the Holocaust firsthand.

“I can remember having so many different Holocaust survivors visit my class in elementary school and my grandparents sharing their personal stories of them being in concentration camps or escaping Nazi Germany,” Panitch said. “And you hear the firsthand accounts and it’s not this date or this thing that happened in history books but it’s real person’s story.”

Panitch is a member of the Bronfman Center, a Jewish student life organization at NYU. But even with direct exposure and involvement in Jewish culture and education, Panitch feels obligated to further the message of her ancestors.

“I remember my parents telling me, ‘you’re so fortunate to being hearing this firsthand and your children won’t have that. It’s your obligation to pass that on,’” Panitch said. “So for me it’s just trying to hold on to that personal aspect of it and not feel like it’s just another instance of the persecution of Jews and we need to not pass on just the number, six million Jews, but the stories behind them.”

One of those stories was voiced by Elie Wiesel, a survivor and fervent voice in the Jewish community, who died at the age of 87 in July 2016. For 22-year-old Spitzer, Wiesel embodied the message of survivors of the Holocaust. And now that he’s gone, Spitzer says its up to him and his generation to carry this message so that moment in history is never repeated.

“My kids will go to all the exhibits and museums and visit Poland like I did, as difficult as it was, it was important to know where we came from and our history,” Spitzer said. “(The Holocaust) was such a formative event in bringing me to where I am.”

For Orbach-Smith, another worry lies in the recent rise of anti-Semitic rhetoric and white supremacy, especially once there are no living survivors to represent the result of the bombast.

“My worst fear is that the world of my children and grandchildren will be like the world of my parents and grandparents and I feel guilty and distraught that my life has been this charmed period of sympathy for Jews in the wake of the holocaust,” Orbach-Smith said. “I sort of coasted through and now once again the rise of this ugliness. I never dreamed that this would be possible.”

But the now-grandmother believes that continued storytelling and empathy from future generations will help combat prejudice and repeated history.

“Time plays a role here in remembering tragedies more than anything else,” Orbach-Smith said.