CONTENT WARNING: Themes will touch on pregnancy loss, grief, and trauma.

After her miscarriage, Kristen Moore struggled with post-partum depression, grief, and anger. She had planned to come out of the pregnancy with a baby girl, Evangeline, but what she got instead was a bill for $1,200 not including the $75 copay.

“I was mad. It’s so much trauma and so much money on the other end of something that it’s surreal,” said Moore.

She didn’t expect a miscarriage to be this expensive.

Even with insurance, treatments can carry expensive copays and out of pocket expenses. For the 26% of pregnancies that end in miscarriage, this means sometimes paying thousands of dollars.

Depending on the kind of insurance and the site of service, miscarriage treatments like a dilation and curettage comonly known as D&C, a procedure in which the contents of the uterus are surgically removed, can range from $2,900 upwards of $9,100 before insurance according to Healthcare Bluebook.

While D&C’s are covered by insurance and are not considered an elective procedure, the site of service can bring the price point up “significantly,” said Dr. Michael Nimaroff, the senior vice president for OB-GYN at Northwell Health.

It’s the site of service that makes “the biggest difference [in cost],” said Nimaroff.

The high cost of miscarriage treatments is not the only burden people who give birth face.

As abortion rights across the country, especially in the South, face restrictions, and Roe v. Wade faces a potential overturn, access to miscarriage treatments is also in limbo.

Pro-life, anti-abortion Conservative legislators are actively trying to tighten restrictions on access to medications like misoprostol and mifepristone which are both used for abortion and sometimes called “the abortion pill.”But this means people miscarrying and in need of these medications will likely have a harder time getting access to them.

And without these medications, people might have to turn to hospitals, surgicenters, or clinics for expensive D&C’s.

Clinics are less expensive than hospitals, but with the increased closure of clinics across the country as anti-abortion legislation is passed, that option is also likely to become less accessible and more detrimental to low income and people of color, who are disproportionately affected by clinic closures, according to research from University of California at San Francisco.

As a result, people might have to travel to different states to receive care if they cannot access clinics in their home state, adding to the already high financial burden of miscarriage.

The journey to pregnancy

Moore, an associate professor at the University of Buffalo, and her husband had been trying to have a baby since 2013, but were told by a fertility specialist in 2016 that natural birth wasn’t possible. They successfully had a son through in vitro fertilization (IVF) after moving to Buffalo in 2018, and were shocked when they found out they became pregnant naturally in May of 2021. Kristen was 40 years old.

“We were excited. We were scared. We were like, what the f–k just happened?” said Moore.

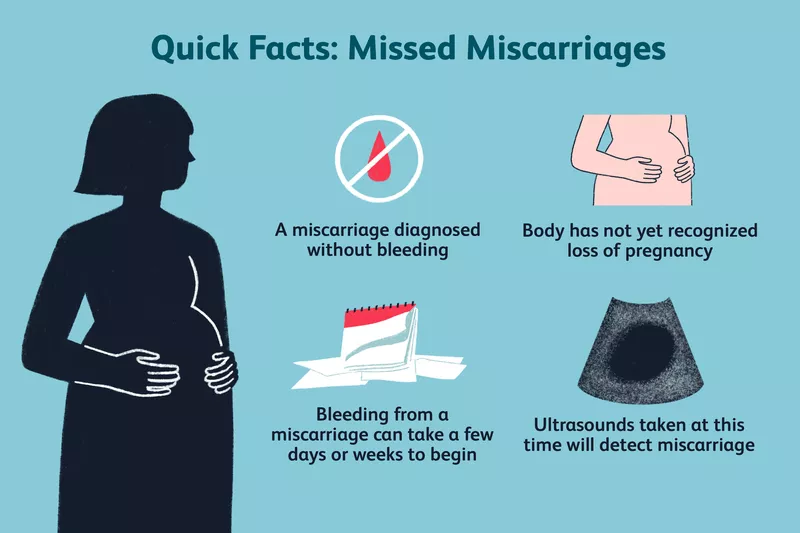

After Moore started spotting at 12 weeks, she booked an ultrasound to check on the status of her pregnancy.

On her way to the appointment, she listened to Brandi Carlile’s memoir, which has songs interspersed between chapters. The song “The Mother” came up, a song Carlile had written about being a mother to her daughter, Evangeline. Moore took it as a sign that the baby would be okay.

“I was like, no, this baby is going to be okay. This is going to be fine. We’ll call her Evangeline and it’ll be perfect because this is sort of a sign,” she said.

But when the ultrasound technician went quiet, Moore knew something was wrong.

“She was like, ‘Hey, I’m not getting a heartbeat.’ This is normally where we’ll let you listen to the heartbeat. We can skip that?” said Moore.

After listening to silence with the ultrasound technician, and getting confirmation from the doctor that there was no heartbeat, Moore knew her pregnancy had ended.

A pharmacy’s refusal, a medication’s failure

Moore’s midwife presented her with three treatment options to remove the fetus: wait for the pregnancy to pass naturally, take misoprostol, a medication that induces the passing of the pregnancy, or get a D&C.

Moore opted for misoprostol, something “less invasive, but more control,” she said. Her midwife instructed her on how to use the medication, and her husband picked it up for her from the pharmacy without trouble.

Misoprostol, along with mifepristone, is is a safe and effective way to end early pregnancies and is used to aid in a miscarriage. At less than $10 on average, misoprostol is the most affordable option, but it does require a prescription.

Trouble began when the instructions on the medication pamphlet didn’t match up with what Moore’s midwife said, so she called the pharmacy to ask for clarification. But the pharmacist refused to give Moore instructions on how to use the medication.

“She was basically like, I’m not authorized to give you directions tied to that kind of use” said Moore. “It felt like she was like, Oh, you’re trying to abort your own child, no, I’m not going to tell you how to do that. I said, I’m told that this can be used to support miscarriage and she was just like, I can’t give you any of that information.”

Pharmacists are supposed to provide counseling to patients on the proper use of misoprostol, according to the Pharmacy Times. And when it comes to emergency contraception, New York State law prohibits pharmacists from “obstructing patient access to medication without a medical justification” or because of religious, moral, or ethical reasoning.

Frustrated and confused by the pharmacist’s refusal to help, Moore called her midwife who walked her through the process, which turned out to be grueling and unsuccessful.

“It’s basically like giving birth. I waited and I waited and I waited and it was really painful. And I still didn’t pass anything that I thought was a baby,” said Moore.

She took a second dose of the medication on the recommendation of her midwife and said goodbye to her husband and son, who were leaving for Michigan to visit family.

Misoprostol has an 87 percent success rate for people who are 10-11 weeks pregnant. And if you’re given an extra dose, as Moore was, it works 98 percent of the time. But when the second dose didn’t work, Moore was left with only one other option: get a D&C.

The most obvious place to get the D&C done was in New York State, but without her husband she had no one to pick her up after the procedure. She considered asking a friend to drive her, but hesitated.

“We moved to Buffalo in 2018. And while I have friends here, I don’t have the kind of friends who you’d be like, Hey, I might bleed all over your car, can you pick me up? I don’t have those,” she said.

She was able to find a doctor in Michigan who took her insurance, and she flew to Michigan for her miscarriage, where she had family support and someone to watch her son.

Moore felt scared that she would miscarry while on the plane, as she had already been slowly miscarrying over the past week and a half because of the two doses of misoprostol.

“There was a real chance that I would have passed the baby [on the plane],” said Moore.

The surgery, copay, and travel expenses were financially unexpected, but, she said, she’s lucky to be able to pay for the surgery without going into debt.

“We keep a really good savings and a really good sort of cushion for emergencies. But if it had been a decade ago, I don’t know what I would have done,” said Moore.

After putting off paying the bill because “paying the bill was saying, well, this [pregnancy] is over,” Moore took to Twitter where she shared her experience in a thread that would gain over 100,000 likes, over 20,000 retweets, and over 1,500 quote tweets from people who had also experienced the unexpected financial and emotional cost of miscarriage.

Today, I paid over $1000 out of pocket for my miscarriage. They didn’t tell me it would cost so much to lose a baby. Here are other things they don’t tell you about miscarriages. A thread based on my experience. CW: miscarriage & infertility.

— Kristen R. Moore (@kristen4moore) November 1, 2021

“I wasn’t trying to go viral. I just felt like there needed to be someplace for someone to say the thing that happens to women and other birthing people,” she said.

Comments

It’s a very difficult situation for a woman. It takes a lot of time for her, sometimes a couple of weeks to really realize and accept what’s happening or what happened