Local governments across the country, including New York City, are spending millions to promote environmentalism in low-income communities, from recycling to organic eating to energy conservation. But many of those who live in the communities say those programs feel distant and irrelevant to the daily realities of their lives.

“A lot of Spanish people really don’t care,” said Neal Figueroa, 17, of East Harlem. “Around here, it’s like a joke.” Figueroa said he and his friends frequently litter on the streets.

The New York City government is investing money for Green advertisement campaigns, programs and buildings, and more New Yorkers are taking steps to join the trend.

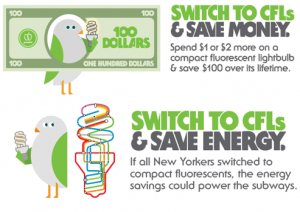

Posters encourage subway commuters to “Switch & Save” and programs such as the Manhattan Borough President’s Go Green initiatives aim to show that going green is for everyone — even those who think they can’t afford it. However, change has been slow for some families.

Waiting outside Andrea’s Hair Design in East Harlem for her hair appointment, Anna Lanza and her friends Sandra Martinez and Aramonita Seda talked about going green. The Puerto Rican women discussed one component of the environmentally friendly movement: organic foods.

“If you going to die, you going to die,” said Seda, a 53-year-old from Central Halrem. “Doesn’t matter if you eat organic.”

For Lanza, 50, it’s a matter of cost. She said she prefers to shop at corner stores and fruit stands because the food is cheaper.

“I can’t afford organic food,” she said. Lanza lives with her husband and four boys, ages 18, 17, 16 and 14, in East Harlem. Her family spends $1,000 per month on food, on top of paying for rent, utilities, credit cards and car payments. “We’re barely making it.”

But going green is not just about eating organic food, said Manhattan Deputy Borough President Rose Pierre-Louis. It is also about carbon footprinting, which is “the impact of how we’re currently living our lives (and how it affects the environment), whether it’s how we’re eating or about congestion.”

Going green refers to any environmentally friendly activity that conserves energy, reduces pollution and saves money. Reducing trash and saving money through sustainable practices, like reusing and recycling, is especially important in low-income communities.

For Lanza’s family, making the effort to go green by recycling seems like a waste of effort and time.

Lanza said it is difficult to recycle because many buildings in her neighborhood do not reinforce it. According to Pierre-Louis, it is the law for every building in New York City to recycle, but in Lanza’s apartment building, there is no recycling bin.

“I don’t mind going green,” she said. “I understand we have a lot of garbage. But they put it all in (the trash), so what’s the point?”

Lanza and her son, Figueroa, both believe environmentalism is too expensive for their family to afford. For example, Figueroa mentioned the extra expense buying trash bags for recycling — money that is wasted because the apartment building does not sort out recyclables from trash.

“It’ll all come down to the neighborhood you live in and your income. Nothing’s (going to) change,” Figueroa said. “I don’t (want to) learn about (going green). I don’t believe in all that stuff.”

Lanza agreed. Her husband makes about $40,000 a year, and she works part-time at American Greetings, earning about $18,000 a year. Her rent is $2,089 a month, and Section 8 pays for 30 percent of it. But even with a dual income and subsidized rent, it is difficult to make ends meet.

Additionally, Lanza now faces the extra financial burden of paying for college. Her oldest son, a high school senior, wants to go to a school that costs $45,000 a year.

To help those with income disparities go green, the borough president’s office created initiatives that work to develop agendas and leverage resources

specific to each community.

A large part of the problem with living in one of these low-income neighborhoods is that “we get the burdens without any of the amenities,” said Elizabeth Yeampierre, president of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance and executive director of United Puerto Rican Organization of Sunset Park.

These burdens include harmful emissions and the health problems that can arise because of them. Sunset Park and Red Hook, for example, are home to a sludge treatment plant; several power plants and waste transfer stations; three highways; and truck traffic — all of which contribute to pollution that can cause health problems like asthma, Yeampierre said.

Additionally, Yeampierre cited the lack of amenities, such as gardens or parks. Amenities are a key component to improving the physical well being of residents in low-income neighborhoods.

“When you have a community that’s struggling, the last thing they (want to) do is plant a tree for the sake of making their neighborhood look good,” she said. “Our kids don’t get enough exercise because there aren’t open spaces. For us, open space is really a quality of life issue.”

Go Green East Harlem has worked to help the community deal with its health burdens while providing more amenities. Since the first Go Green initiative was launched in 2007, Borough President Scott Stringer has spent at least $7.6 million to develop parks, playgrounds and an Asthma Center in East Harlem to help residents who suffer from the harmful effects of air pollution.

The Manhattan borough president’s office has improved access to healthy fruits and vegetables for people at all income levels, Yeampierre said.

“One of the things we’ve done in East Harlem, for example, is start the first ever weekend farmers’ market in East Harlem,” she said.

According to the Manhattan borough president’s office, poor neighborhoods are suffering health risks, such as obesity and diabetes, because of insufficient access to healthy foods.

“East Harlem … has the highest number of fast food restaurants per square mile than anywhere else in New York City,” Pierre-Louis said. “That gets into the issue of ‘food deserts’ meaning that within a close proximity of your home, to be able to access a green market or grocer is a challenge.”

Residents can now purchase fresh fruits and vegetables from vendors with their Electronic Benefit Transfer cards, an electronic system that allows card carriers to purchase products through government benefits.

Araceli Bandoja, 29, said she bought food from the farmers’ market at Franklin Plaza and was pleased with the low cost and high quality.

“It’s a little more cheap and more fresh, and they give a lot,” she said. The vegetables and fruits look “different” from those she bought at nearby neighborhood markets, but “in a good way.”

Still, not everyone knows these options are available in their neighborhoods. Lanza said she is not familiar with the Go Green East Harlem initiative and farmers’ market, but expressed an interest in affordable green options.

Yeampierre said there is a strong interest in low-income, ethnic neighborhoods to learn about going green — not because it may seem trendy, but because those communities recognize they are the ones who suffer most from environmental burdens.

Environmentalism refers to the consumer aspect of going green, which often comes with high price tags, according to Yeampierre. Products that are advertised as green or sustainable may not be affordable, but a sustainable lifestyle can help people save money—a concept many low-income families are already familiar with.

“Poor people are the most sustainable people there are,” Yeampierre said. “We’re the ones most likely to make food stretch or use our materials in creative ways because we’ve always had to do a lot with a little.” Shopping for old clothes at thrift stores, for example, is a sustainable practice.

This creativity with reusing cheap, available resources translates to environmental consciousness. Going green has to be relevant to their everyday lives and struggles, she said.

“That’s how we get communities to participate and get involved,” Yeampierre said. “All of them care about their children and the health of their elders.”

Not everyone in East Harlem is against the green movement.

“In our building, we are almost the only one family that recycle,” Bandoja said. “We like to live better to get a better future for our kids.”

Bandoja lives in an East Harlem housing project with her husband and two children. She has not heard about the Go Green East Harlem initiative, but her family tries to be green by recycling. She and her husband have taught their children about recycling and energy conservation. Her two sons, Axel and Oswaldo, are also learning about going green at school.

“You have to recycle the newspapers and bottles and any glass,” said 8-year-old Axel. “If we don’t recycle, the earth is not going to be healthy and clean.”

Comments

[…] Green movement targets low-income communities […]