Since Hurricane Maria struck, water issues have plagued Puerto Rico. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia

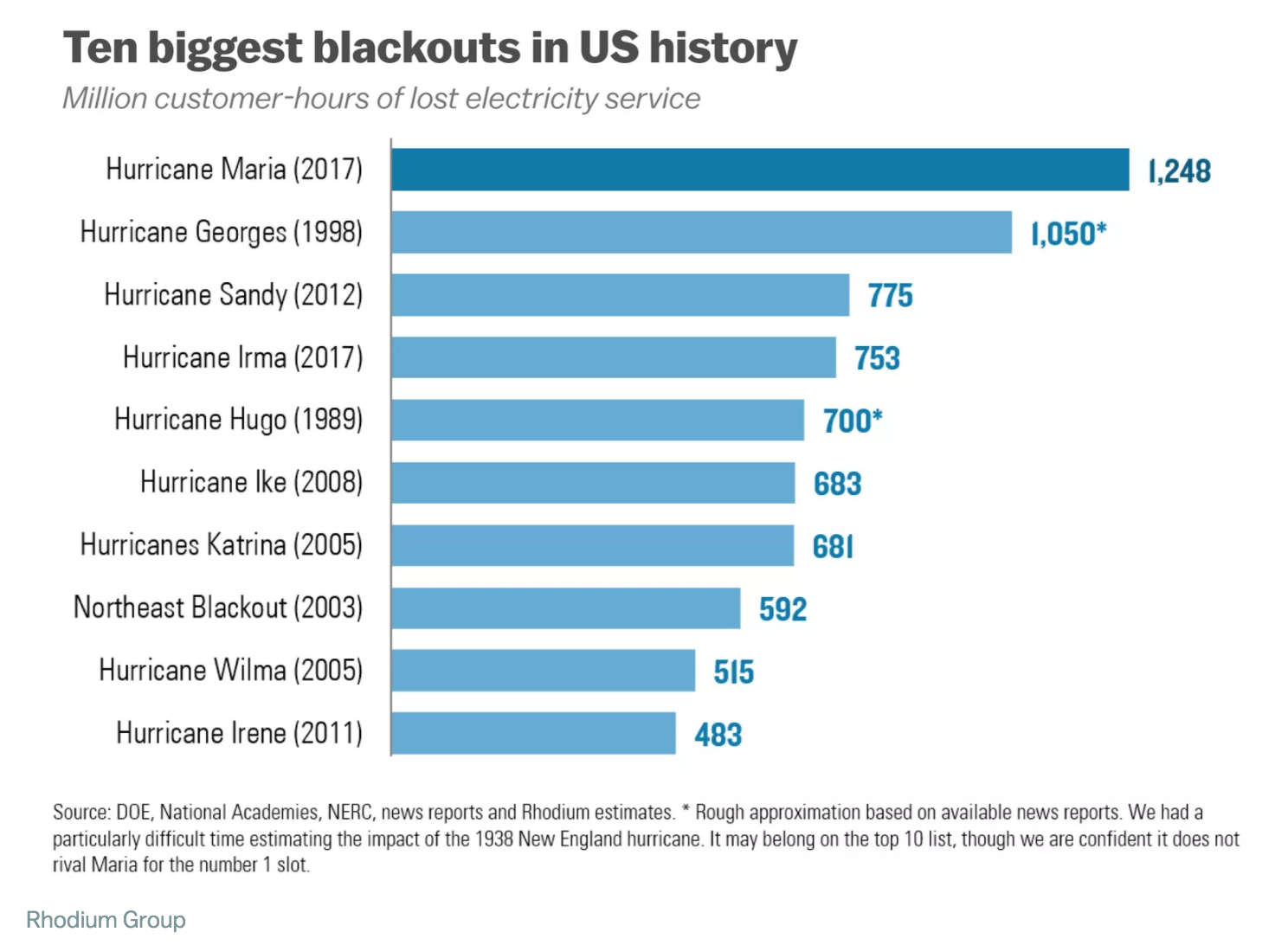

More than 130 days have passed since Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, devastating the island and causing one of the greatest humanitarian and environmental crises of the last decades. Today, electricity still hasn’t been restored across the island and the water situation is even worse.

Steve Tamar, director at Blue Water Task Force Rincon water quality program and vice chair of the Surfrider Rincon Foundation is stationed in the northwestern point of the island where, in many areas, power still hasn’t been restored.

“There’s no power since the hurricane,” said Tamar. “Water was restored to this barrio three weeks ago, but it’s kind of intermittent, it comes and goes.”

“There’s no power since the hurricane,” said Tamar. “Water was restored to this barrio three weeks ago, but it’s kind of intermittent, it comes and goes.”

According to the Associated Press, in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, raw sewage poured into the streams and rivers of the island, contaminating the water. The presence of toxic waste in the water leaking from the 23 Superfund sites on the island also increased threats of bacterial diseases, like leptospirosis, which caused two deaths after the hurricane.

Because of this, chlorine is being used to clean the water, causing the islanders to deal with yet another problem. According to Scientific American, excessive chlorine in water may cause respiratory issues and increase the risk of bladder, rectal and breast cancers.

“They’re hyper chlorinating the entire system specifically to kill microorganisms and it’s changing the pH in the water,” said Tamar. “And we’re recommending people not to drink it or to boil it first and let it sit and outgas.”

Tamar and his team are testing the water for quality and installing water treatment units where necessary or, when it’s more efficient, distributing domestic home filters house by house.

The island’s battered infrastructure continues to be a problem and many believe it won’t be able to handle the increasing threat of climate change if no changes are made.

Specifically, Tamar believes that the electrical transmission lines should be buried and not exposed to wind damage.

“It’s having electricity above ground that’s a real liability to islands like this,” said Paul Strum, director of Ridge to Reefs organization. “Certainly Puerto Rico’s infrastructure was old and badly maintained, but when you have trees and power lines that are above ground it doesn’t matter how good that infrastructure is, it’s going to have severe damages from the storm.”

With the Trump Administration recently cutting funding for the EPA and increasing environmental policy rollbacks such as toxic waste protocols, many organizations on the ground feel that government agencies haven’t done enough to help.

“Both the federal agencies and the Puerto Rican agencies are doing very little,” said Tamar. “The government’s already saying ‘we’re gonna sell the electric system’ cause they can’t handle it.”

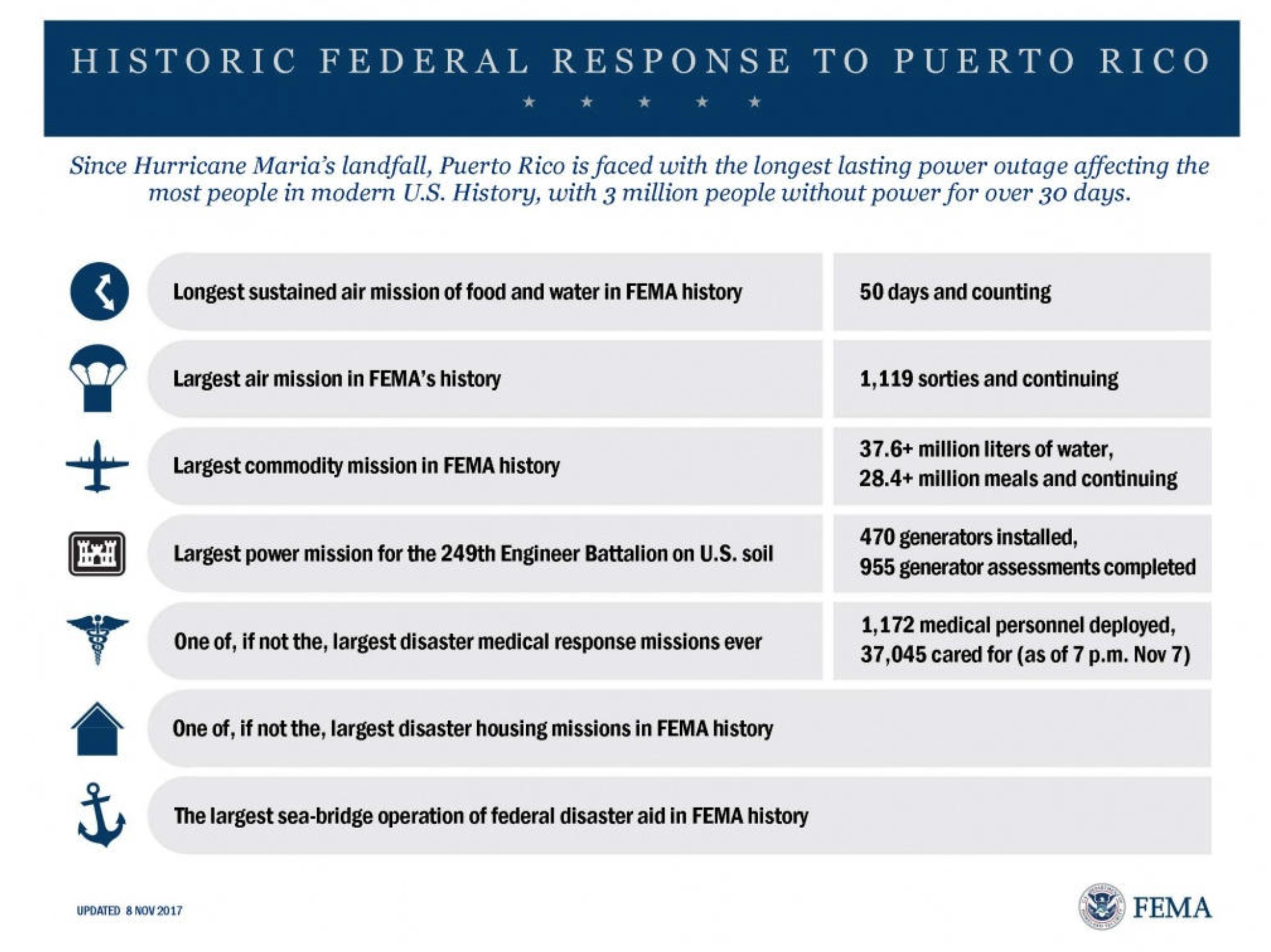

According to FEMA, Puerto Rico was one of their largest missions yet.

But, in the thick of it, organizations felt it was easier to act independently.

“We didn’t waste a lot of time with FEMA or EPA. There was too much heat on the ground to bother with coordination with large bureaucracies,” said Sturm. “It wasn’t a productive use of our time.”

Both the reconstruction and the resiliency building are happening as a bottom-up process, where organizations work to manage relief projects on their own.

“My personal thing has been going up to these remote barrios and distributing little solar powered lights,” said Tamar. “Every time I go up there I empty out the vehicle, giving hundreds away at a time.”

According to Ridge to Reefs the island is starting to develop pockets of areas using renewable energy. Even though they’re still extraordinarily vulnerable, having renewable energy sources means that power is not attached to the grid, avoiding failure if anything were to happen, and functioning as a backup system in case of emergency.

“Water pumping stations, sewage treatment facilities, schools, hospitals, nursing homes, things like that should really be off the grid and not dependent on the power system,” said Sturm.

With the bureaucracy gridlock, lack of transparency in managing funds and a generally dysfunctional system, many still think it will take time before things are back to normal.

“People are still working four months later, they’re rebuilding, still replanting their farms,” said Sturm. “And in many instances they’re trying to do it with limited water and energy. They’re expected to be ongoing for another 6 to 12 months.”

Others, however, are less optimistic about timing but are counting on the community’s willingness to stick together and help each other.

“We’re not being overly hopeful of recovery being completed anytime soon,” said Tamar. “Things are really, really messed up here, but the community is coming together to solve its own problems.”